(Bloomberg) — Regardless of which party wins Britain’s July 4 general election, a massive debt fallout awaits, severely limiting the scope for poll-leading Labour and the ruling Conservatives to govern.

Most read articles on Bloomberg

This financial constraint is the result of four years of crisis spending – first to rescue jobs and businesses during the Covid-19 pandemic, and then to help families cope with the cost of living shock after Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Rishi Sunak was the architect of this wasteful response as Chancellor of the Exchequer during the pandemic and then as Chancellor, but it is also a problem for the Labour Party, which supported him from start to finish.

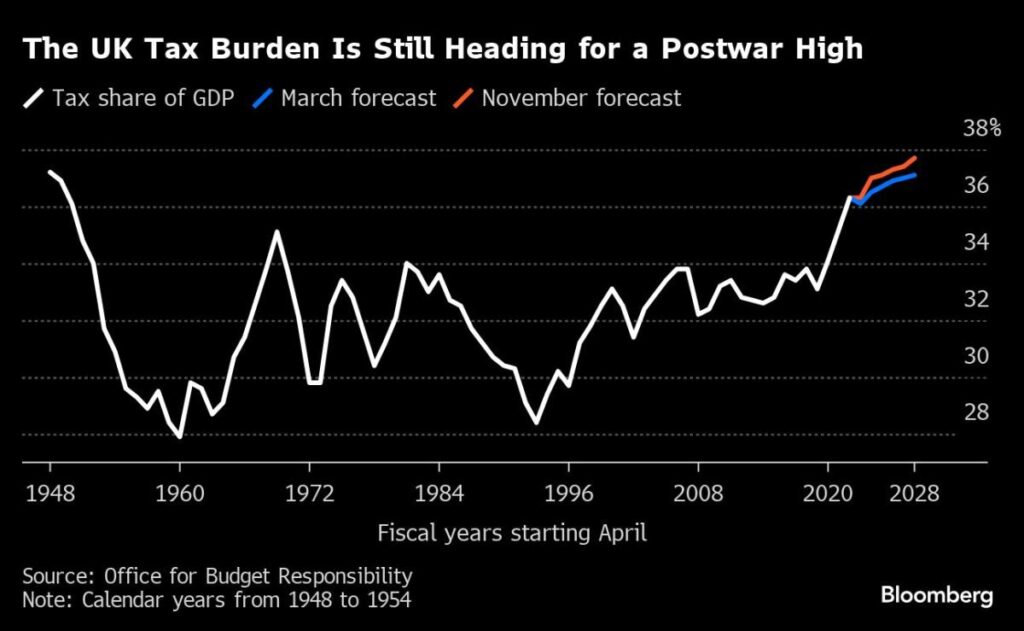

The resulting dire situation is clear: Britain's crumbling public services are in desperate need of funds, yet taxes are at their highest post-war levels, the national debt is at its highest since the early 1960s, and servicing it in a high-interest world is costing an extra 60 billion pounds ($76 billion) a year — the equivalent of the entire defence budget — and yet not a single bullet has been fired.

The spending catapulted Mr Sunak to fame and briefly made him the country's most popular politician, but Britain's resulting debt problems mean there are no easy options for the winner of a general election in five weeks' time.

“People were hoping for generous support during the coronavirus pandemic but rising debt and interest costs are now untenable,” said Hetal Mehta, head of economic research at St James's Place.

Labour's shadow chancellor, Rachel Reeves, said the new government would face the worst economic crisis since the second world war and ruled out raising major taxes, while the Conservatives planned to cut them.

But public services need new money to clear patient backlogs, fix schools, repair an overflowing prison system and fill potholes. Both parties say growth is the remedy, and Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, has described the policy as a “blessing of the moment.”

For James Smith, research director at the Resolution Foundation, the first week of the campaign has been a disappointment. “There's a disconnect with the economic reality of the budget,” he said. “Both parties are blaming each other for poor fiscal management, rather than addressing how to reduce the debt.”

To be sure, the UK is not the only major developed country with a heavy debt burden after four years of crisis, but it has suffered the deepest scars: Between 2019 and 2023, the UK will see the biggest increase in net debt as a percentage of GDP of any G7 country, according to the International Monetary Fund, largely as a result of policy choices.

The IMF said Britain was the most generous G7 country outside the US in its support for the coronavirus pandemic and the second most generous after Italy during the energy crisis. The government's bailout measures during the succession of disasters have cost the country around £400 billion, and servicing the extra debt is costing the country around £15 billion a year.

Britain's spending may have been big, but it has not translated into better economic outcomes, with the virus's toll clearly visible in its growth and jobs data, and Britain's post-pandemic recovery has been the slowest of any G7 country except Germany.

Moreover, in contrast to other G7 countries, the UK's labour force participation rate has yet to recover to pre-pandemic levels. The number of people not in the labour force increased by nearly one million to 9.4 million, of which 700,000 were due to long-term illness. A third of people not in the labour force aged 16-64 cited health problems as the reason for being out of the labour force.

“Lower labor force participation is hurting growth and has fiscal implications,” said Vicky Price, chief economic adviser at the Centre for Economics and Business Research. “With fewer people working, tax revenues are hit.”

Not all of Britain's problems are the fault of COVID-19 and the rising cost of living: business investment has been sluggish for years after the 2016 vote to leave the EU, and trade activity has slowed since Britain formally left the bloc in 2021, which orthodox economics argues will reduce potential growth.

British households have also become more cautious since the COVID-19 outbreak. Living standards have fallen, but spending has fallen further as people have put more money into savings. According to analysis by the Resolution Foundation, ordinary Britons have reduced their consumer debt by the equivalent of £48 billion since the pandemic began. Similar trends have been seen in France and Germany, and the US has seen a spending boom.

The structure of Britain's debt makes things worse: a quarter of the government's bonds are inflation-linked, meaning the cost of borrowing £600 billion rises with prices. Inflation is usually good for borrowers because it allows the nominal size of the economy to grow faster and reduces loans as a share of national income while the amount of debt remains constant.

The UK inflated its debt that way in both the 1950s and 1970s, and the same happened to the US, Germany, Italy, Japan and Canada between 2021 and 2023. Of the G7, only the UK and France saw their debt rise as a percentage of GDP during their recent inflationary shocks.

“This means that this period of high inflation has made the government's fiscal position worse, rather than improving it,” Resolution said in a paper published this month.

Inflation is back close to the 2% target, energy costs are down and Covid-19 is a bitter memory – the economy may be “looking better”, as Chancellor Sunak claims, but the legacy of the past four years will tie the next government's hands.

Most read articles on Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 Bloomberg LP