Stories of massive data breaches at well-known companies such as Bank of America, American Family Insurance, and T-Mobile are dominating national news. The Internet Crime Report, compiled annually by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, shows the alarming nature of cybercrime, with the number of formal charges increasing by more than 300% each year and reported economic losses expected to exceed $10 billion annually. warning of an increase in demand.

Meanwhile, there are an estimated 3.5 million cybersecurity job openings worldwide, approximately 750,000 of which are in the United States.

Dangerous hackers are stealing our data and money.

Jan Shoshtaishvili, associate professor of computer science and engineering at Arizona State University's Ira A. Fulton School of Engineering, came to stop them.

Shoshtaishvili plans to fill the recruiting pipeline with highly qualified cybersecurity professionals who can defeat hackers. Because these pros have learned to play the game and win.

His innovative project, pwn.college, is a unique combination of an educational curriculum, a competitive practice environment, and a set of communication tools that support collaborative student learning. Fulton His School has developed an effective system for training the next generation of cybersecurity professionals.

And the world is paying attention.

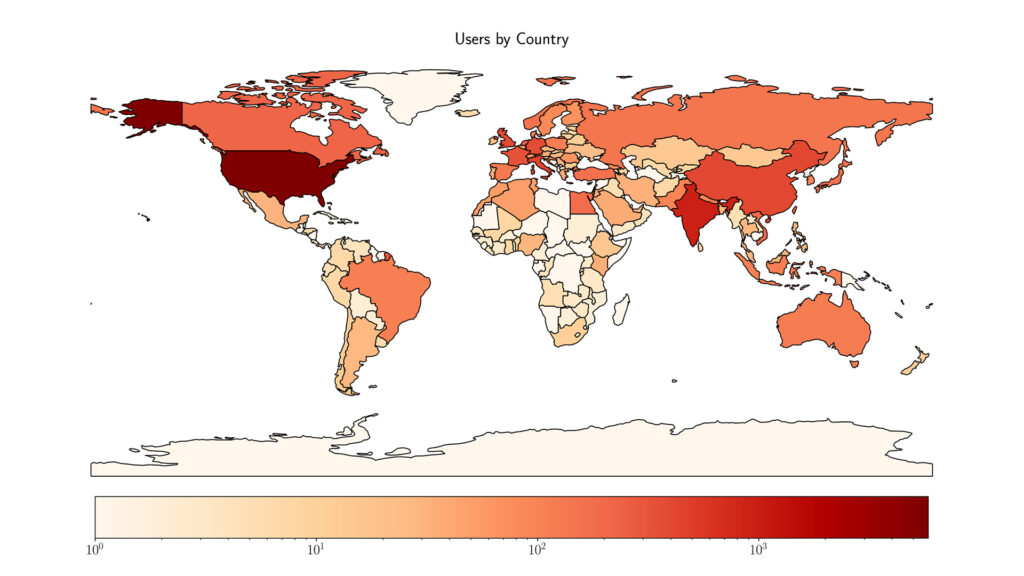

Today, pwn.college is used in 145 countries and is on its way to becoming the gold standard for cybersecurity training. The idea for this project was inspired by Shoshtaishvili's own experience in computer science, when he was a student of computer science, where he became enthusiastic about participating in his competition “Capture the Flag”.

“I learned a programming language called assembly through a series of hacking challenges, and it was a complete game-changer for me,” he says. “We were able to uncover the fundamentals of computing in a way that we had never experienced before.”

Capture the Flag in real life is an outdoor game in which two teams compete to be the first to retrieve a flag or marker from the opposing team's territory or designated base.

Similar activities can be performed in computing environments where software engineers hide cryptographic tokens (usually short lines of code) in parts of systems that are supposed to be secure. To win the game, hackers must identify security vulnerabilities, circumvent them, and find hidden lines of code.

“The great thing about teaching from this offensive perspective is that if students can hack a particular program, they know that particular attack,” Shoshitaishvili says. “It becomes much easier to design defenses that block attacks. Such competition builds confidence and skill.”

However, many organizations, such as popular hacking convention operator DEF CON, host competitive events and conferences several times a year.

When Shoshtaishvili began designing his own educational curriculum, he realized that it would never be enough.

practice makes perfect

As combating the rise in cybercrime requires new approaches, Shoshtaishvili and colleague Adam Doupe, associate professor of computer science and director of the Center for Cybersecurity and Trusted Foundations at the Fulton School, asked them to discuss what the future holds for cybersecurity training.

“I said something like, 'What if we teach cybersecurity and hacking skills the same way we teach sports?'” When you practice for a sport, you practice the basics over and over again. Let it become natural,” says Doupe.

The two settled on a concept for an online dojo (Japanese for a hall where karate and judo are practiced) that would resonate with students who are fans of martial arts movies, anime, and manga.

Early on, Shoshtaishvili was approached by Connor Nelson, a doctoral student in computer science, who wanted to join him on the ground floor of this groundbreaking project. Nelson took Shoshtaishvili's curriculum and implemented it on his dojo's website.

The pwn.college site was originally designed to work with the in-person curriculum of live ASU classes such as CSE 365 Intro to Cybersecurity and CSE 598 Advanced Software Exploitation. Shoshtaishvili transformed his lesson plans into a series of modules that students could work on alongside their lessons. Each consists of different resources, including tutorials and recorded introductions. To complete the module, students must successfully complete a series of capture-the-flag exercises. Results are displayed on a leaderboard to foster a spirit of friendly competition.

Just like in a real dojo, students can earn belts every time they complete a module. Entry-level computer science students start at white belt. After completing all modules, student hackers can earn a blue belt. Shoshtaishvili held obiding ceremonies throughout each semester to recognize progress in the dojo.

Everything went well.

Then the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic occurred.

Shoshitaishvili (both left) and computer science PhD student Connor Nelson (both right) complete a cybersecurity training module at the 2023 DEF CON Capture the Flag Afterparty in Las Vegas preparing to present pwn.college belts to students who have completed the program (pictured left) and the 2024 ASU campus (right).Image courtesy of Connor Nelson

When the student is ready, the master appears

With much of the world in lockdown and most university campuses closed, Shoshtaishvili was forced to consider how to provide vital instruction to students stuck at home.

He noticed that many schools were using Zoom to conduct online classes, but Nelson, who will complete his PhD researching pwn.college, streams his lectures on Twitch and is already We advocated building an online community on Discord, two popular platforms. Connection with electronic games soured relations with hackers.

“Zoom works well enough, but the atmosphere is a little boring and social. But Twitch is fun. It's made for gamers!” Nelson says. “Also, to be honest, answering student questions and getting feedback asynchronously in his text-based chat room is a million times more effective than interrupting his microphone online and shuffling his game.” That’s the point.”

When Shoshtaishvili was live-streaming a lecture in lockdown, he noticed that the controlled chaos resonated with students. One of his most popular Twitch lectures features an instructor discussing return-oriented programming with his baby daughter in a sling on his back.

The pwn.college Discord server is also popular with student hackers.

“The Discord community is a great place to bounce ideas off people and ask for tips when you get stuck,” says Samuel Zhu, graduate student in computer science and white belt in pwn.college. says. “The community there is very helpful even without giving you answers. People are there for the struggle and the learning, and that's something I'm very invested in as well.”

Even after the pandemic subsides and we return to in-person learning, Shoshitaishvili saw great value in maintaining an online community. He believes that having a variety of learning methods is an important part of a project's success.

“There's an interesting online phenomenon where some people never ask questions in class. They're afraid of it,” he says. “But they'll be asking questions on Twitch all day long. They'll be chatting and sharing code on his Discord. These tools allow a lot of people to fully participate.”

The final piece of the puzzle was the development of SENSA.I.is a personalized tutor powered by artificial intelligence that develops insights from the Dojo platform to help students progress when they need help.

“Students may not want to contact Discord for every little thing, or it may be that they are stuck in the middle of the night,” Shoshitaishvili said. “Users can now ask questions to her SENSA.I. Ask for help. ”

With SENSA.I. Instead, the dojo is always open.

pwn.college is used in 145 countries and provides cybersecurity curriculum to universities around the world.Image courtesy of Connor Nelson

The future is now

Universities around the world have begun using pwn.college as part of their cybersecurity curriculum, with the program being implemented in schools in the UK, Italy, Singapore, South Korea, Georgia, and India.

In 2023, cybersecurity students around the world spent more than 1.5 million hours in dojo training. In just a few short years, the site has grown from just a few people to nearly 14,000 registered users, with over 800 belts awarded each year.

Mr. Shoshtaishvili is also the Associate Director of Workforce Development at the Center for Cybersecurity and Trusted Foundations, where he focuses on potential applications of the pwn.college system for the corporate and government sectors.

“Adequately protecting the nation and the world from cybersecurity threats is one of the most pressing challenges in computer science today,” said Ross Maciejewski, director of the School of Computing and Augmented Intelligence. Masu. “Shoshtaishvili’s work will ensure the rapid growth of the talent needed to tackle these challenges.”

Branden Yang, a fourth-year undergraduate studying computer science and cybersecurity at Greenbelt, believes pwn.college will help him in life after college.

“I think more than anything, pwn.college really taught me how to learn,” he says. “I know how to ask good, specific questions and get information about techniques. I understand cybersecurity concepts and how to use them to solve real-world problems. Masu.”