This rebroadcast originally aired on February 29, 2024.

A recent report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office reveals poor living conditions inside military barracks – from mold and exposed sewage, to broken windows, nonexistent HVAC systems and more.

Today, On Point: U.S. military barracks are in shambles. Will the government take action?

Guests

Elizabeth Field, chief operating officer for the Elizabeth Dole Foundation, an organization supporting military caregivers. Co-author of the GAO report “Military Barracks: Poor Living Conditions Undermine Quality of Life and Readiness.”

Raymond F. DuBois, senior advisor at the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS).

Also Featured

Salem Ezz, software engineer at the Civil-Military Innovation Institute. Co-creator of the Mold Conditions Awareness Tool.

Transcript

Part I

MEGHNA CHAKRABARTI: That buzz you get on the first day of a new chapter in your life. Salem Ezz felt it. It was 2019, and he’d made the decision. He enlisted in the United States Army. As his first posting as an American soldier, Fort Stewart, about 40 miles southwest of Savannah, Georgia. It’s the largest army installation east of the Mississippi.

It covers almost 280,000 acres and is home to approximately 15,000 active-duty soldiers and 16,000 of their family members. Ezz, as an unmarried young man, was assigned to soldier barracks.

SALEM EZZ: Concrete, white walls, gray floors, just that normal kind of like tile.

CHAKRABARTI: Like a ’70s dorm room, he says.

EZZ: Two soldiers per room.

There’s not really a divide between your space and their space. A very tiny kitchenette, no range, no stove. A microwave on top of the fridge and then a small bathroom.

CHAKRABARTI: Ezz took it in stride. He knew you don’t exactly join the army to live in the lap of luxury. But there was one thing.

EZZ: There was definitely like a little bit of a, kind of a … smell in the air, if you will.

Kind of sharp, like something was growing maybe sometimes.

CHAKRABARTI: Something was and is growing in the barracks. Mold. On the walls, in the HVAC system, in the bathrooms, showers, toilets, closets. The mold grew on bags, turned mattresses green and black. Another soldier who spoke to Military.com said mold, quote, “consumed his room.”

EZZ: Definitely the first time I saw the barracks. I was, like, a little in shock, definitely, 100%.

CHAKRABARTI: This is On Point. I’m Meghna Chakrabarti. Substandard military housing is not a new problem for the Department of Defense. In fact, it is a very old one, going back decades, well into the 1990s. And it has caused a national outcry before.

In 2019, Reuters uncovered fraud on a massive scale. Private contractor Balfour Beatty Communities, which managed 43,000 homes for military families, was found to have falsified maintenance records, ignored maintenance requests, even pleas from families to clean up homes riddled with mold, asbestos, crumbling ceilings, and filth.

Following a congressional investigation and multiple lawsuits, Balfour Beatty pleaded guilty to fraud. And in 2021 agreed to pay the Defense Department more than $64 million in fines. Then Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy vowed to improve the DOD’s oversight of housing contractors. He pledged to find the money to build new family housing, and the Army began requiring home inspections for safety hazards.

“There was a breakdown over the last decade,” McCarthy told Reuters. “These are hard lessons learned, but we’re trying to dig out quickly,” end quote. More than a decade before that, in 2007, the Washington Post broke a story about horrendous living conditions in barracks for wounded soldiers at Walter Reed Army Medical Center. In the congressional hearings that swiftly followed, lawmakers didn’t even try to hold back their anger.

REP. PAUL HODES: I think this is a massive failure in competence and command.

LT GEN. KEVIN KILEY: Yes, sir.

HODES: When is the first time you heard about these kinds of problems?

KILEY: When I saw the articles in the Washington Post.

CHAKRABARTI: That was New Hampshire Representative Paul Hodes at those 2007 hearings. He was grilling Lieutenant General Kevin Kiley, then Army Surgeon General and former commander at Walter Reed.

Kiley said that even though he lived across the street from Walter Reed, as commander, he never personally inspected the barracks. He had subordinate commanders across the Army’s medical command who did that.

But lawmakers, including Ohio Congressman Mike Turner, couldn’t quite believe that the chain of information within the chain of command had broken so completely that Kiley had no clue that soldiers who’d fought and been wounded in Iraq and Afghanistan were trying to convalesce in Bethesda military housing, infested with mold and mice.

MICHAEL TURNER: Okay, well, General Kiley, then this gets back to, to my question of, of, of, uh, systems. You said you do not do inspections. Um. I don’t think anyone would think that the system that you have in place as a manager of an organization would be sufficient if your answer is that you don’t do inspections, but yet you still did not know. I mean, there’s something wrong with the organizational structure if we all have to hear from the Washington Post.

KILEY: Yes, sir.

CHAKRABARTI: So clearly, many times over the past many years, the Defense Department has been made aware of systemic and bureaucratic failures in its oversight of military housing. And yet somehow, the same military, capable of launching highly sophisticated, coordinated strikes anywhere in the world within minutes, continues to have difficulty keeping track of housing conditions on its own domestic bases.

Back at Fort Stewart in Georgia in 2019, and more than a decade after the Walter Reed scandal, infantryman Salem Ezz says the barracks were as bad as ever. Recall, as an unmarried soldier, Ezz was living in what’s called unaccompanied housing, or UH, as it’s called within the military. And these barracks were not getting the same kind of national media attention that Walter Reed or the family housing crisis had.

With the exception of Military.com, The Army Times, and other military press. Plus, dedicated reporting by local journalists living near the bases. Ezz says it felt like the conditions where he lived were often met with a shrug.

EZZ: It was like yeah, duh, what are we going to do about it? The reaction was like futility, essentially.

CHAKRABARTI: The Army did make efforts to remedy Fort Stewart’s broken-down housing. In October 2022, a Department of Public Works team spent 90 days on site inspecting and remediating more than 1,100 cases of mold. Base leaders even went so far as to order a stand down day for senior noncommissioned officers to address concerns raised by soldiers.

At that stand down day, Command Sergeant Major Quentin Fenderson told the officers that something had snapped in the chain of accountability. Barracks inspections were not happening the way they used to when the officers themselves were fresh recruits.

FENDERSON: What’s unfortunate about this whole conversation is the fact that, everybody in here, at some point in your life, some point in your career, I should say, somebody came in your room and checked your room as a soldier.

CHAKRABARTI: “Why are we not checking our soldiers’ rooms?,” Fenderson said. Quote, “I’m going to walk through your barracks. I need you to do your jobs. I’m going to do mine.” End quote. Bill McGovern, mold specialist with Fort Stewart’s Department of Public Works team, added that beating the mold problem required a team effort from command all the way down to individual soldiers.

We need to hear from the occupants that they have a problem in their room.

CHAKRABARTI: Salem Ezz says there is an app that soldiers can use to report problems in their rooms. However, it only works for conventional repairs.

EZZ: You can put a work order in it and someone will come in and do it. But people don’t have X-ray vision and can see whether or not their HVAC system is working.

And by the time it’s a problem, there’s mold everywhere. Those are things that soldiers can’t see, but affects them.

CHAKRABARTI: That was in October of 2022. At the time, no soldier had reported health issues due to mold, according to an official video posted on Fort Stewart’s YouTube page. But Fort Stewart’s mold problem was not solved.

In fact, for the Army as a whole, it was about to get worse.

SOLDIER: I’m sick maybe twice a month just with the same issue, a chest cold, that I’ve been told from our doctors that it’s likely from mold or what’s in the air that’s coming through our HVAC system.

CHAKRABARTI: This soldier spoke to local television station WSAV just five months ago, September 2023.

He feared reprisal. And requested anonymity.

SOLDIER: Soldiers were hospitalized. And even when they were hospitalized, they were told to move back into that room that they were in. Weeks later, they were finally moved out, and even though they were moved out of that room, they were still put into another room that may not have a lot of mold, but that mold is still being circulated through the HVAC system.

CHAKRABARTI: The soldiers spoke out a few days after the General Accounting Office released a damning new report on September 20, 2023. The 118-page investigation documents wretched conditions, such as mold and overflowing sewage. Not just at Fort Stewart, but in barracks at bases across the country. Moreover, the report concludes that, quote, “while DOD spends billions of dollars annually on its facilities, it’s unable to identify how much funding goes towards barracks,” end quote.

CHAKRABARTI: In a few moments, you’ll hear a lot more about that GAO report from one of its authors. And so the cycle begins again. Just like in 2007 and 2019, a new report is revealing systemic failures in military housing. And just like before, Defense Department officials are promising action and accountability.

This time around, it was Assistant Defense Secretary Brendan Owens who did just that before a House Armed Services subcommittee earlier this month.

OWENS: The DOD has in too many instances failed to live up to our role in making sure the housing we provide honors the commitment of the service members and enables them to bring their best versions of themselves to their critical missions.

CHAKRABARTI: Former infantryman Salem has told us it’s a readiness killer.

EZZ: The conditions certainly were terrible for morale. Terrible for people’s devotion to what they were doing and the worth of it.

CHAKRABBARTI: And, once again, members of Congress are expressing outrage. This time around, it was House Armed Services Subcommittee Chair, Florida Representative Michael Waltz, at that hearing this month.

WALTZ: Who was fired? What base commander, what facility manager, was anybody relieved or fired because of this?

OWENS: Chairman Waltz, I’m not aware of anyone who was.

WALTZ: Do you find that acceptable? I mean a hallmark of military leadership, of any leadership, is accountability and consequences.

OWENS: Yes, I totally agree with that. And I think that as leaders, through the NDAA –

WALTZ: But no one from the Secretary down to your level, down to the Services, down to a base commander, nobody has actually been held accountable, no one has actually been relieved or fired.

OWENS: Not that I’m actually aware of.

WALTZ: I would submit to you that that may be a critical part of the problem.

CHAKRABARTI: In a moment, we’ll go even deeper into that new GAO report with an investigator who visited military bases across the country. And we’ll talk with a former Defense Department official about what it will really take for the Pentagon to make sweeping and systemic improvements to military housing for all U.S. soldiers stay with us.

Part II

CHAKRABARTI: Today, we’re talking about the latest report of abysmal living conditions in soldier barracks at U.S. domestic military bases. And joining us now is Elizabeth Field. Just last year, at the end of last year, she’s the one who authored the GAO report titled “Military Barracks: Poor Living Conditions Undermine Quality of Life and Readiness.”

At the time, she was director of the Defense Capabilities and Management Office at the U.S. Government Accountability Office. She’s now chief operating officer for the Elizabeth Dole Foundation. Elizabeth Field, welcome to On Point.

ELIZABETH FIELD: Thanks for having me.

CHAKRABARTI: So you visited ten military bases across the country.

I’m wondering if you could tell us in more detail what you saw. One of the first photographs in your report shows a barracks bathroom overflowing with sewage. It looks like feces is all over the floor. What did you see?

FIELD: You’re right. That is exactly what was happening at that barracks.

And our understanding, and I should state from the outset that I cannot speak for GAO, but I was the author of that report, that problem with the overflowing sewage happened routinely, the soldiers living in that barracks told us, every few weeks or so. And unfortunately, that was not an isolated incident.

We saw barracks that had broken windows, broken air conditioning, unclean drinking water, really a host of serious health and safety condition problems.

CHAKRABARTI: And the mold, tell us more about that because it keeps coming up in all the stories that we’ve been hearing.

FIELD: It does.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah, go ahead.

FIELD: Sure. Mold was one of the most common issues that we heard and also observed.

There were real health concerns associated with the mold and mildew, although I have to say that there were also some conversations we had with defense officials who questioned whether it really was mold, or whether the mold was associated with health problems. And that is one of the issues here, which is that there can be at times a lack of seriousness with which defense officials take these concerns.

CHAKRABARTI: How bad actually, was it in these various spaces? And actually, first of all, I should emphasize even though we’ve mentioned the army a couple of times, this is a problem that the Pentagon admits is across the services, right? But you’ve described that they didn’t look like they should be on U.S. soil at all, that they reminded you of facilities that you’d actually seen overseas?

FIELD: Yeah, that’s right. It was a jarring experience to feel this Deja vu. And not realize why. And then realize it felt like some of the worst barracks I had seen in Afghanistan. There are some barracks that are not in bad condition. I should state it’s not every single facility, but it is across the services, and it is across the country.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah. Absolutely good, point taken. There are thousands and thousands of barracks on U.S. bases across the country. So this isn’t a 100% problem, but it is a pervasive one.

Just in, I still want to give listeners a deeper sense of exactly what we’re talking about. So when you say it reminded you of some of the worst facilities you saw in Afghanistan. What were those facilities like?

FIELD: Oh my goodness. Broken doors throughout, broken showers, mold everywhere. Not functioning HVAC systems, broken lights throughout, concrete walls that were crumbling, really bad conditions.

And in fact, at this one location, we heard that some of the sailors, this was a Navy facility, I think, thought that they had not had water, warm water for two weeks, and they thought that was part of the training regimen, but it was just that they did not have a working system to give them hot water.

CHAKRABARTI: So you also, in compiling this report, you also had a discussion group with service members. What did they say? Even maybe the most reticent ones, who you talk about a Marine who basically didn’t say much, but then when he did talk, it really took you aback.

FIELD: That’s right. So in these discussion groups, it was not uncommon for us, from the outset, to hear concerns about everything from a concern about a lack of safety to feeling extreme temperatures in the barracks, but this one Marine just really stuck with me. Because he wouldn’t join his peers in saying that he didn’t like the conditions he was living in.

And he said, because it was the first home he’d had. That was not one where he had grown up living in poverty, but then at the end, when we said, what’s one thing you would change? He said, I would appreciate having clean drinking water.

CHAKRABARTI: Wow. And also the fact that he said it’s not the first place I lived that looked like when I was living in poverty.

That’s certainly the standard for soldier housing that we have, must be higher than that. Now, I want to stress that, of course, we did contact the Pentagon multiple times via phone and email. We sent them a detailed list of questions about plans to improve soldier barracks, how much it would cost, how much they know and don’t know about barracks conditions.

They wouldn’t answer our questions directly or provide anyone to appear on the air today, but they did refer us to a report that was just released 10 days ago called the Resilient and Healthy Defense Communities Strategy, which we had looked at. And we’ll talk a little bit more about that in the show.

But Elizabeth, so you visited 10 bases. How confident are you in extrapolating the conditions you saw at those 10 bases to other facilities, military facilities across the country?

FIELD: I am comfortable for a number of reasons. The first is that there have been other studies, including internal to the Defense Department, that have found problems with the barracks across the board, including a few years ago when they were conducting surveys of service members living in the barracks, which they no longer do, but were at the time.

And those pointed to some real problems. The other thing I would say is that we found systemic problems with the ways in which the Defense Department was assessing the barracks’ condition. Trying to maintain the condition of the barracks. So I feel quite comfortable, even though, again, not every single barracks facility is a problematic facility.

It’s certainly not isolated to those 10 installations. And I should note, one of the biggest problems here is that across the Defense Department, there is a $137 billion deferred maintenance backlog. There is no way the department is going to spend its way out of that backlog. And the facilities that most often end up on the cutting room floor when it comes to maintaining facilities, are things like barracks and child care centers and dining facilities.

CHAKRABARTI: Is it because they’re considered not mission critical? Why would you do that to soldiers and their families?

FIELD: No, you’re absolutely right. It is because installation officials and those above them face some really tough choices about what to spend somewhat limited maintenance dollars on. Are you going to spend it on fixing a runway?

So your planes can fly or appear, so you can use your ships or are you going to spend it on barracks? That is a extremely difficult trade off. But it’s also quite frankly a sad trade off and one that I think has moral and equity consequences.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah. We’re going to talk about this more a little bit later, but to hear the Defense Department say the money isn’t there is a hard sell for me. Because the overall Defense budget, as you well know, is north of $860 billion.

And maybe how that money is appropriated is the problem, but I don’t think you or I or anyone listening to this is just going to accept passively that a budget that’s nearing overall a trillion dollars in the next couple of years can’t dig up the money to fix barracks. Now Elizabeth, there’s another important thing I want to ask you. And in terms of the systemic failures, we will talk about those in detail, but there’s something very critical and perhaps not adequately understood about the soldier barracks that you inspected.

These are for soldiers without families. And so is it fair to say that almost every member of the United States military? Perhaps early in their careers, will have or will be living in these barracks at some point in time? And does that form an initial impression of what military service is like?

FIELD: Absolutely. So all enlisted service members start their careers in the barracks, and it is their first interaction with the military. It is, for many of them, their first home away from home. And it leaves an impression on them about what it is like to live in the military, to have a career in the military.

And it certainly is something that they take back with them when they go home. And share their experience with their family or with their friends who might be considering joining the military. But I think there is also, and I referenced this before, a moral imperative here, which is that we all know that a lot of the young men and women who decide to enlist in the military, they do so not because they have a lot of options, and this is their lifelong dream.

It might be their only option out of high school, or their best option. And so it is really imperative that we honor that sacrifice and commitment to serving their country by at least giving them clean, safe, comfortable housing.

CHAKRABARTI: You’re listening to Elizabeth Field. She’s the person who authored this really damning report from the General Accounting Office that was released late last year called “Military Barracks: Poor Living Conditions Undermine Quality of Life and Readiness.” You should definitely take a look at it. We have a link to it at On Point Radio. I want to get the voice in of another a person who has been impacted by this. Today we’re focusing on soldier barracks, but of course, on base, it’s part of a much larger problem that, as we know, historically has also had a major impact on soldiers’ families.

So returning to Fort Stewart for just a second here, family members also living on base there in Georgia, they’re also struggling with this pervasive mold problem. So at the end of last year, this wife and mother spoke under the condition of anonymity with local television station WSAV. Now her husband has been deployed for a year and a half and she’s living in on-base housing with two children under the age of three.

SOLDIER’S WIFE: And there’s just mold growing all over my son’s sneakers, my husband’s gear, his brand-new boots, OCP’s. Everything. And I’m like, what do I do? So I contacted maintenance. They said watch what you can. You can try and make a claim with us and make us liable. But there’s no guarantee we’re going to help you.

The entire 18-month span that we have dealt with all of these issues has really dramatically hurt. As a military family member, we live in a very inconsistent life. And the one thing that is provided to us as security and safety is housing. And we’re supposed to be able to trust it. And it’s not. We can’t.

CHAKRABARTI: I’m Meghna Chakrabarti. This is On Point. I’d like to bring Raymond DuBois into the conversation now. He served as deputy undersecretary of defense for installations and environment from 2001 to 2004. He’s also former acting undersecretary of the Army, a position he held from 2005 to 2006, and he’s currently senior advisor at the Center for Strategic & International Studies.

Raymond DuBois, welcome to On Point.

RAYMOND DuBOIS: Thanks Meghna, happy to be here.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah. So first of all, help us understand. Obviously major problems with its overall infrastructure, but specifically military housing has been dogging the Pentagon for decades, right? Even before your time. And then we mentioned 2007, the Walter Reed scandal, 2018 and ’19, the private contractor and family housing scandal.

And now here with Elizabeth’s report, we have yet another report of just abysmal living conditions in soldier barracks. Everyone acknowledges that the DOD has known about this problem for a long time, and yet in the GAO report from September, one of the first findings that Elizabeth published was DOD does not reliably assess conditions and some barracks are substandard. They don’t even really know the conditions of a lot of these barracks. How is that possible, after all of this time?

DuBOIS: First of all, I want to compliment Elizabeth and her staff for writing an excellent report. Let me just begin by repeating some of what she said, in terms of the awful conditions that occur in terms of barracks, unaccompanied housing, family housing has a direct relationship to the 3 R’s. Readiness, recruitment and retention.

Now, one would think that the leadership of the Department of Defense and specifically the three military departments, Army, Navy, Air Force and they have said this repeatedly. Those are key issues of their responsibility and concern, break. There are three issues when it comes to the billion dollars of deferred maintenance that I was presented with in 2001 and the three areas are leadership, management and money.

Now, as the deputy undersecretary, I immediately, when I was appointed, I called in the three assistant service secretaries for installations and environment. And I said, we’re going to meet every week. And I want you to share with us your issues that you see, but first and foremost, I want you to go out to the field and inspect.

Now, I wasn’t their direct boss, but because I reported to the big boss, the Secretary of Defense, they got the message. But the issue from the top leadership is very important. They set policies, they set the programs, they should require accountability down the chain of command, but most important, they set the budget. There are two pots of money that go into housing barracks and installations. One is military construction, which is new construction. And that’s a separate budget under a separate appropriations subcommittee. And No. 2, there is money for maintenance that comes out of a very large pot of money called O&M, operations and maintenance.

Now, what has happened over the years? Continually, and this is the key issue, is when money is tight, especially when you’re fighting wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. As Elizabeth pointed out, when it comes to runways or piers or even the maintenance and repair of vehicles, tactical vehicles, money, oftentimes, while it was originally slated for housing for barracks gets stolen. And I use that word advisedly.

It gets taken from one account and it’s spent elsewhere.

CHAKRABARTI: Raymond DuBois, hang on for just a second. I hate to interrupt you, but we just have to take a quick break and we’ll continue this important part of the conversation when we come back. This is On Point.

Part III

CHAKRABARTI: Today we are talking about the most recent report about abysmal living conditions, this time in soldier barracks at U.S. domestic military bases across the country. Barracks full of mold, broken down HVAC systems, sewage regularly overflowing in bathrooms, and why, after report over the course of several decades, the Pentagon still hasn’t got a complete handle on providing American soldiers and their families with housing that’s up to standard.

I’m joined today by Elizabeth Field. She authored this GAO report and now she’s a Chief Operating Officer at the Elizabeth Dole Foundation. And Raymond DuBois is with us as well as former Deputy Undersecretary of Defense and former Acting Undersecretary of the Army. Now at the Center for Strategic & International Studies.

And Raymond, I wanted to let you pick up your thought about, you say, use the word advisedly, you said. But that when money is tight, funds are quote, stolen out of the bucket that should be used for operations and maintenance and put elsewhere. So finish that thought.

DuBOIS: I will use the euphemism instead of stolen the senior leadership in the military departments will reprioritize O&M dollars. And what the money issue is very important. Because it’s tied to leadership at the very top. Leadership at the very top has to ensure that the monies that were originally allocated to maintaining and repairing base infrastructure, including barracks, must be actually obligated and spent. And what I found out is that because of pressure from other parts of the Army in particular, but it’s true about the Navy and the Air Force and the Marine Corps, money got shifted away from where it was supposed to be spent.

So that gets back to the, so we say 3 overlapping Venn diagrams, leadership, management and money. Management, the middle level, if you will, for instance, the Army installation management command used to report directly to the chief of staff of the Army, but a decision was made several years ago by the secretary of the Army to move it to be a subordinate command to the Army material command.

I would suggest that was a mistake. You’ve got, if you care about readiness, recruitment and retention. And the causal relationship with bad housing and insufficient oversight. You’ve got to have a senior officer directly reporting to the chief of staff.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah.

DuBOIS: Now, as the GAO report said, and somewhat charitably, I might add, there’s insufficient oversight.

There’s trouble with data collection and analysis, as Elizabeth pointed out, and these issues are only overcome by focus at the senior level.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah.

DuBOIS: But it’s also focused at the installation level, in terms of inspection, in terms of data collection, taking surveys on post and as we know in the military, it’s bad news does not travel up the chain of command easily.

CHAKRABARTI: Clearly.

DuBOIS: There’s a reticence to report. And as in the beginning, first or second level, from the Sergeant Dubois to his Command Sergeant Major, to the Company Commander. Things get sanitized as it goes up the chain of command. This is an issue of leadership and it’s an issue of management.

CHAKRABARTI: Can I just jump in here for a second, Raymond? Because I really want to turn your points back to Elizabeth’s, to hear what she says. Because I also want to let folks know that this most recent GAO report that Elizabeth authored, it was done not just because the GAO want to do a surprise pop up inspection of bases.

It was required by the 2022 National Defense Authorization Act. The government itself was like, we need to keep on top of this terrible housing problem. Across U.S. bases. That is why the GAO report happened. And Elizabeth, to speak more specifically about your findings regarding lack of information, which comes up.

Over and over again in this housing debacle for decades. Some of your findings include DOD does not have complete funding information to make informed decisions. That they had requested $15 billion for overall facility sustainment for fiscal 2024. But could not identify how much would be spent towards barracks.

And then you also find that DOD does not track information on the condition of barracks. Okay, that one really stuns me, after all this time. Again, do you have any insight on how that is even possible, a good 20-plus years into this ongoing military housing crisis?

FIELD: I think the Venn diagram, Mr. DuBois was talking about is spot on.

And I think when it comes to things like understanding and assessing installation condition, a real problem here is that no one was paying attention to make sure that the barracks were being inspected with any sort of regularity or frequency that was appropriate. That the number of systems that were being inspected was sufficient, or that the inspectors even had the appropriate expertise to be able to say what the condition of an installation is.

And to give you just one example, all barracks facilities are given a condition score of somewhere between 0 and 100. 100 being perfect condition. My team and I went to more than one installation to visit barracks that had high scores. For example, one barracks facility that had a score of 86. So you would think it’s in pretty, pretty good condition. Quarter of the rooms and that facility had broken air conditioning.

They also had broken windows, broken lights. So clearly, there’s a problem with the condition score, but I also want to throw in one additional pot of money. Mr. Dubois talked about military construction funding and operation and maintenance funding. O&M, which certainly are directly related to building or maintaining barracks.

There’s also military personnel funding. And one of the things that my team and I discovered is that the defense department spends over $1 billion in any given year, roughly. To basically put junior enlisted service members who should be living in the barracks out in the local economy where they are on their own to find housing.

It is a real problem. The defense department did not even know it was spending that money until we did that analysis.

CHAKRABARTI: While distressing, not surprising, I have to say, because as we’ve talked about on this show over and over again, the Pentagon has never even passed an audit. So it is not shocking to hear that they don’t exactly know where all the money is going to.

And if I can be frank with both of you, we do a lot of shows in which I have to just take deep breaths and try to remain calm. This is one of them for sure, because as I mentioned earlier, the American taxpayer is looking at a defense budget that is going to push a trillion dollars overall in the coming years.

What are we paying for? Half of that’s going to defense contractors. The other half is, it’s got to go to a lot of different things. I’m not saying that I’m questioning exactly how the money’s being spent. I’m questioning that we don’t even know where it’s going. Maybe the problem is with insight and database transparency, with appropriations.

Whatever it is. And I get that infrastructure is hard. The DOD itself says they’re in charge of a million permanent and rotational beds for soldiers overall. But going to the moon was hard too, and yet we, in the course of less than a decade, this country went from barely being able to toss a tin can into low orbit, to putting men on the moon.

And so maybe, Raymond, I’m just rephrasing what you’re saying here. Because I hear lawmakers, congressmen and women, the president, paying hypocritical lip service to not the military overall, but members of the United States military. We’ve gotten to the point where we’re fetishizing the idea of military power in this country, but while we constantly say, may God save our troops, why don’t we just leave God out of it? And instead say maybe may the United States Pentagon save our troops from living in mold infested facilities.

Where does the buck actually stop, Raymond? It has to stop somewhere.

DuBOIS: There was a reference earlier to the Walter Reed Hospital issue. I had left the Army when that occurred, but I obviously read the front page of the Washington Post that morning, too. The Secretary of the Army, then Secretary of the Army, Fran Harvey was called on the carpet.

And Bob Gates, eventually, Bob Gates essentially fired him. Because he said Secretary Harvey, you’re not paying attention to some of the most important issues as it pertains to readiness recruitment and retention. Now, was it entirely Fran Harvey’s fault? No. There are a number of people in the Army who should be held accountable.

I found that exchange with the Congress about was anybody fired by my successor several times removed to be a little bit troubling. Because there should be some people fired or retired or resignation. Now, let me stop there and say the assistant chief of staff for the Marine Corps, assistant commandant of the Marine Corps General Chris Mahoney very recently made a public statement, complete inspection of all barracks worldwide. He said, we need, we do not have, and we need to have a baseline understanding of conditions. And by March 15, 15 days from today, a master gunnery sergeant or higher is going to conduct an inspection outside of the chain of command.

In other words, they’re going to bring in a senior NCO from outside that particular chain of command on that particular installation to do actually a hands-on, eyeballs on inspection. I would like to see the vice chief of staff of the Army, the vice commander chief of naval operations, the vice chief of staff of the air force make a similar public commitment.

These kinds of things, you have to compliment Congressman Rogers and Smith and Bacon and Houlihan, who wrote that letter about quality of life. And you have to compliment the GAO, but the real, the buck stops at the secretaries of the military departments, all installations belong to one of those three secretaries, except one.

And the one, of course, is the Pentagon reservation. That’s the only one that belongs to the secretary of defense. So those 3 service secretaries have got to take it upon themselves to make this a priority.

CHAKRABARTI: Yes.

DuBOIS: And to hold people accountable.

CHAKRABARTI: To be fair, obviously, also after the family housing crisis from 2019, the Pentagon, particularly the army, made a lot of strides forward, right?

And they have responded again, as I said, the Pentagon referred us back to the Resilient and Healthy Defense Community Strategy, which they just released a week and a half ago. So there’s at least some sort of verbal responsiveness going on. And I want to just play one more bit of tape. This is from the hearing earlier this month at the House Armed Services Subcommittee.

And Rachel Jacobson, who’s the current Assistant Army Secretary for Installations, Energy and the Environment, laid out the plans that the Army has for modernizing and repairing thousands of barracks under its control.

RACHEL JACOBSON: We will take full advantage of the new authority Congress has given us to replace barracks that are beyond repair, using restoration modernization funding.

This approach to inventory capitalization will save time and money. So we thank Congress for that authority. Second, we will build a robust workforce of trained civilian barracks managers. We will no longer ask soldiers to perform these functions as a collateral duty. Third, we are taking a hard look at changing the way we do business.

This includes how we design our barracks spaces to give soldiers better living experiences. And it includes a robust business case analysis of barracks privatization. The Army is ready to move forward with a privatized junior enlisted barracks project at Fort Irwin.

CHAKRABARTI: So that’s Rachel Jacobson, Assistant Army Secretary for Installations.

Obviously that word privatization, we could do a whole other show about that, and military housing, and maybe we will in the future, but she was talking about a pilot program at Fort Irwin. Now Raymond and Elizabeth, unfortunately we only have about two minutes left, and I want to split it between the two of you.

Elizabeth, in the GAO report, there’s more than 30 recommendations for what the Pentagon should do to really solve, or at least get a handle on this barracks problem, in particular. Can you give us what you think some of the most important recommendations are?

FIELD: I am actually going to point to something that is not a recommendation in that report. Because at the time, the department, the Defense Department was exploring privatization.

And we did not want to get out ahead of that study. But in my personal opinion, there is no way that the military services can fully address all of the problems with the barracks without privatization. It’s not a silver bullet. And by all means, those private developers will need to be overseen. Very closely. They need to be watched like a hawk, but this cannot be solved through the traditional military construction process. And the strategies that have just been put out sound good, but I will believe it when I see it.

CHAKRABARTI: Raymond. While you have the last minute here, same question.

DuBOIS: Okay, Meghna. Thank you.

Elizabeth is quite right. I took a pilot program under President Clinton, Secretary Cohen in 2001 under President Bush and Secretary Rumsfeld to privatize family housing. As Elizabeth says, we’ll never catch up there, there’s tens of billions of dollars. That first of all, Congress just won’t appropriate.

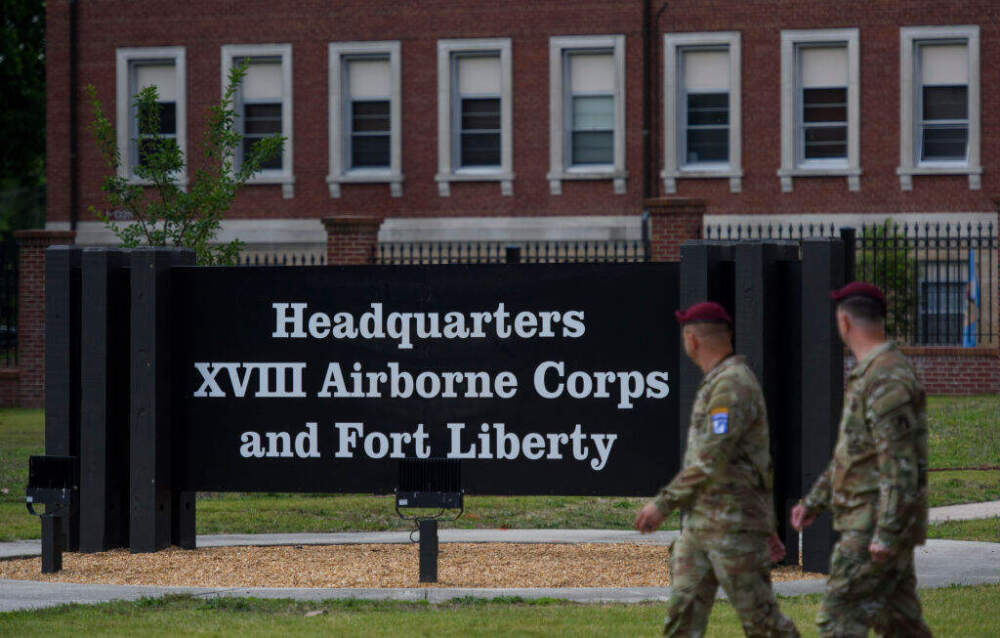

And we’ve got to privatize. We’ve got to use the capital markets to do this. That is something that is carefully managed. The other thing that I want to say here. And what bothers me, and I know this is going to be taken as a criticism. But recently I read about Fort Liberty, formerly known as Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and what the Corps of Engineers is doing there.

But as I read the article, it said, Oh, yes, we’re going to build new 18th Airborne Corps headquarters. And I guess if I were the Secretary of the Army, I might say, excuse me. We’re going to do barracks and family housing before we build the three-star general a new headquarters. But that’s, I can easily say that sitting outside of the five-sided building, but there’s an example of optics, rhetoric. You can have all the plans and programs you want. But you’ve got to execute, and you’ve got to hold accountable people.