In a corner of a crowded convention hall filled with the latest game-building technology, Lewis Castle stumbles upon an old Apple II with a black-and-white monitor running games from floppy disks.

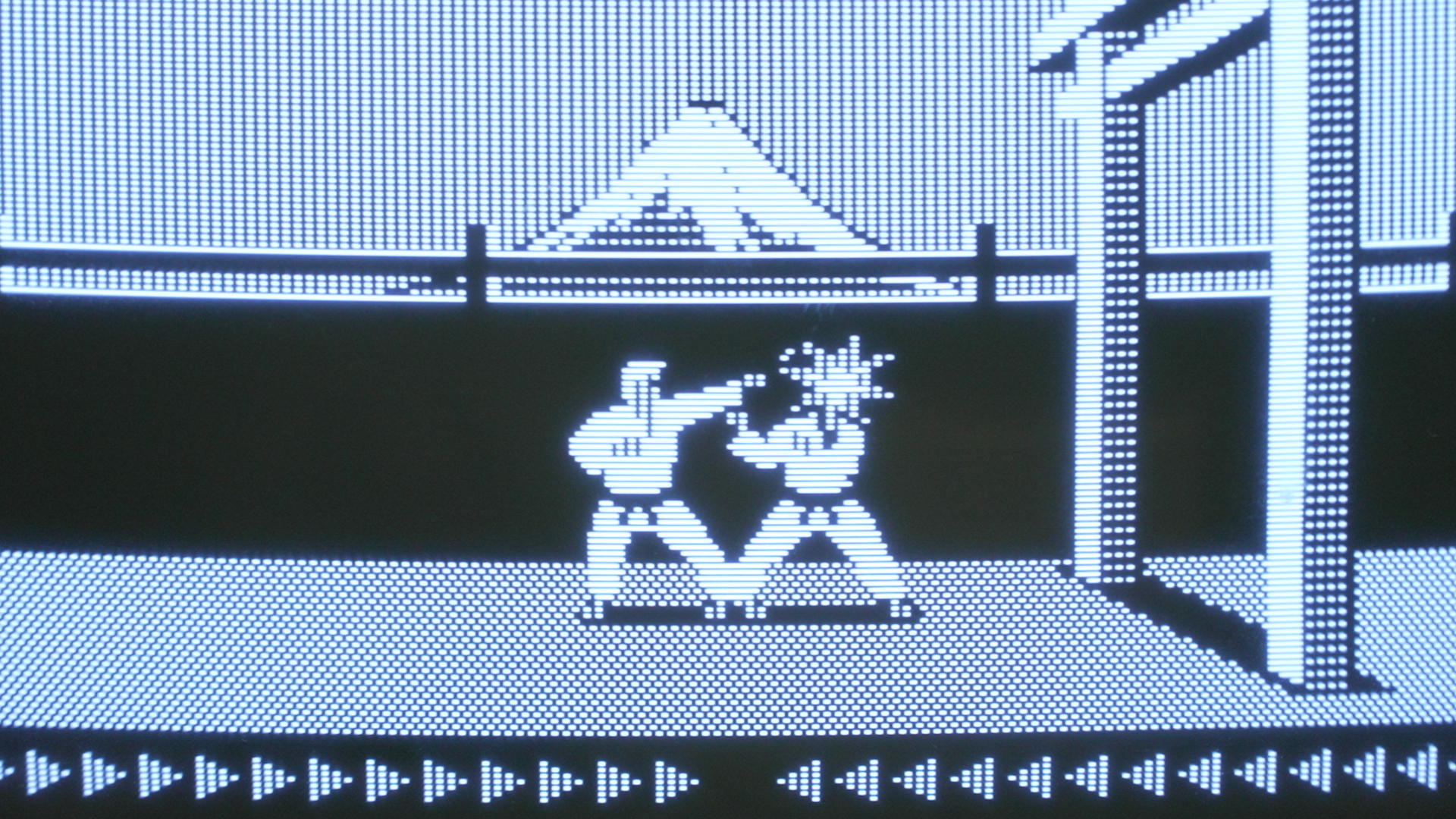

That game was Karateka. An early martial arts game, published years before the arcade hit Street Fighter II became a mainstream fighting game. And it reminded Castle of a story.

“They actually did a lot of rotoscoping,” he explained. “They shot film and drew on the film cells to get the movement of the characters.”

Located among booths where actors and dancers perform eye-catching stunts with digital motion-capture cameras, this is one of the games that pioneered this technology using film and paper 40 years ago. I was there.

“When I started in this industry, when game developer conferences started, pretty much everyone had to be a programmer,” he explained. “In the first game, we would draw on graph paper, and then we would whip it up and he would convert it to hexadecimal and input it. There were no mice, no tablets, nothing like that.”

Castle estimates he has created about 150 games over his 40-year career. Some works were huge hits, like “Blade Runner.'' Some were built just for fun, and some appeared as source code printed in early game developer magazines. However, over the years, most of those early games have been lost to time and lost. In an industry that's seriously focused on the future, this turns out to be an incredibly common story.

“Even from 15 years ago, we found that a lot of games were lost,” said Stephanie Hawkins, event director for the annual Game Developers Conference, where Castle serves on the advisory board.

Hawkins said conference organizers have long partnered with the Oakland-based Museum of Digital Entertainment to bring exhibits like the one Karateka had on display into the convention hall. But in 2024, Hawkins said there's a growing feeling that game preservation should be a major theme at conferences, making it a bigger priority for the industry.

classic game first names

The new focus on preserving classic games is music to 36-year-old Wade Rosen's ears. Arriving outside a hotel conference room carrying a backpack and wearing a vintage Atari T-shirt, he doesn't look much like the CEO of a company founded in the 1970s. And that's exactly the point.

“We always joke that we're a 50-year-old startup,” Rosen said.

In 2021, he became CEO of Atari. Probably the most famous name in the short history of the video game industry. Founded in the Bay Area, Atari launched a cartridge-based video computer system in 1977 that brought games like Asteroids and Pac-Man to living rooms around the world.

Although it has since been overshadowed by new consoles from Nintendo and Sega, Atari's legacy shines brightly in the childhood memories of Gen Masu.

“Practically speaking, let's focus on retro, classic games and be the best in the world at that,” he said.

In the early days, games didn't need stories or characters. Those were simpler times, when consoles ran at speeds slower than 1 megahertz and had only a few kilobytes of memory (sometimes less). Still, the developers have managed to create an experience that is fun, challenging, and addictive.

“You don't need to know why you're shooting bugs,” Rosen said, referring to the 1981 Atari classic “Centipede.” “You just jump in and shoot bugs, and it’s fun!”

long overdue sequel

Atari's history is full of firsts, including Lunar Lander, the first arcade game to use vector-based graphics. Now, 45 years later, Atari believes his popular 1979 black-and-white game deserves a sequel.

“This is Lunar Module Beyond,” Rosen explained as he played a demo of the new game on his PC (and crashed the spacecraft several times in the process).

The new game features a character-driven storyline and colorful graphics, and Atari will release it on nearly all modern consoles, including PlayStation, XBOX, and Nintendo Switch. Sequels to other classic games are also in development. But Atari has other ideas.

“We kept hearing from people, 'I have a bunch of old Atari carts, what should I do with them?'”

Who will diss the new Atari?

In late 2023, Atari announced its answer: the Atari 2600+.

Although it's not the company's first retro console, the $130 Atari 2600+ is definitely its most ambitious offering. This is his meticulously crafted 80% scale model of Atari's first home console, with a woodgrain front panel and the old 9-pin controller port. It comes with a joystick that's almost indistinguishable from the original model released in the 1970s, and a cartridge loaded with 10 classic Atari games.

Besides the smaller size and shiny Atari logo, the new console has another important change. It's an HDMI port for connecting to modern TVs. Rosen says Atari is serious about preserving the games of its glory days, and that means building a console that works in today's living rooms. But just as important, he said, is preserving the vintage experience. This is still a cartridge-based console. That is, if you want to play a game, you have to find it in cartridge form.

“What we're finding is a community of people who want that physicality and want to touch and experience the body the way they did when they were kids,” he said. “And those are the people we're trying to appeal to.”

In the months since its launch, Atari has added a set of paddles (knob-like controllers used to play games like Breakout and Pong) to its 2600-plus lineup, as well as a set of paddles coded for the 2600. We've fleshed it out by adding a brand new game called Mr. Run. Jump. With this release, the game, which began as a developer's side project, became the first new Atari game to be released in cartridge format since 1991. And, just like in the old days, it was hand-coded in assembly language (and may have included some drawings). on graph paper).

humans vs robots

Long before advanced graphics tools existed for game development, the best tool was, and still is, human imagination, Castle says.

“There are a lot of great ideas in old games,” he said. “In fact, for almost every new game that comes out that's really exciting, there's actually an older game that inspired it.”

In fact, Castle is so confident in human creativity that he is not worried about the rapid evolution of generative artificial intelligence. On the contrary, he says he welcomes it.

“Our industry is in a bit of a crisis because content development costs have become so high,” he said. “The great thing about[generative]AI is that we can really leverage the talent that we already have to create more things, faster.”

Already at this year's Game Developers Conference, independent studios have shown off games created by AI or featuring AI-assisted game artwork. Kipwak Studios spent just eight months building the first playable version of Wisdom Academy. This is a game where players manage a Hogwarts-like school for young wizards.

“When it comes to art, we are backed by AI,” explained lead developer Guillaume Mezino. “What we do is first sketch… and then we feed that sketch to the AI so it can come up with something better.[Then]we take the art home with us. We work together until we're happy with the product. ”

Castle says he's optimistic that this kind of human-AI collaboration won't eliminate game designers' jobs. In an industry full of creativity, original ideas remain the most valuable currency.

“People imagine what they want to see in their mind's eye,” he says. “I think imagining what could happen, rather than basing things on what has been, is what drives innovation.”

Some ideas are good, some ideas are great. And sometimes ideas become classics.

“Will people still be playing Super Mario World in 100 years?” Rosen asked rhetorically. “That's right. They're going to go back in time and play it out just like we're reading 'Gatsby' today. It's going to be relevant today.”