ORLANDO — When 2013 turned to 2014 and no new college football video games were being made, the people who made the best sports video game about the best sport scattered. Some stayed in Orlando to help make Madden, college football's older, more profitable cousin to the NFL. Others moved on to 2K to make other sports games.

No matter which direction they went, they all wanted the same thing: to create another college football game.

Ben Haumiller was one of the main stars of the last game (NCAA Football 14) before moving on to Madden for a few years. Madden was a great product and certainly sold well, but Haumiller wasn't enthralled by it. By the time the sun went down on the Saturday of Labor Day weekend, the Florida State University graduate who grew up outside Orlando had seen more snaps of college games than he would have in a season of NFL games. So a few years ago, he moved to the business side of EA Sports for two reasons: it got him out of a professional rut, and, more importantly, it got him and some of his former teammates on a path to reviving the game they loved making more than we loved playing it.

“I never thought about leaving [the company]”I knew I'd be back,” Haumiller said.

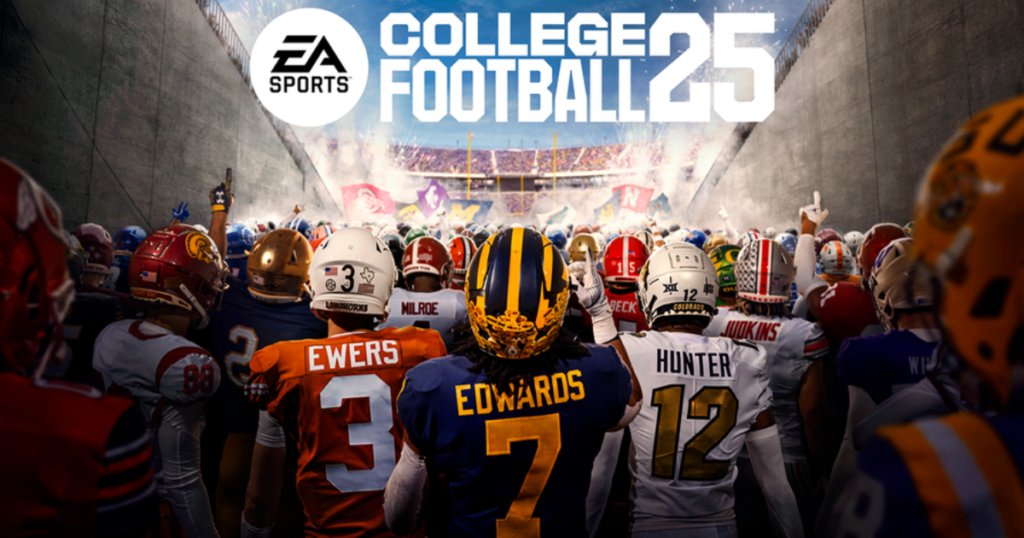

After multiple federal court cases, the passage of 50 new state laws, a 9-0 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Alston v. NCAA, and a paradigm shift in how college sports are run, college sports is indeed back. On July 19th (July 16th if you pre-order the Deluxe Edition or the bundle with Madden), EA Sports College Football 25 will be blasting out of kid's bedrooms, dorm rooms, man caves, and woman sheds across the country.

“It was always a question of when,” said Daryl Holt, senior vice president at EA Sports. “It wasn't a question of if.”

The game originally died because EA Sports had been named as a defendant in former UCLA basketball player Ed O'Bannon's federal lawsuit against the NCAA. EA's college football games used generic players with little disguise to imitate real-life players. For example, the final version of the game featured a quarterback from Texas A&M University who wore the number 2 and was a good scrambler. Everyone knew it was Johnny Manziel, but Manziel had not been paid for the apparent use of his likeness. EA Sports settled the O'Bannon lawsuit in 2014, but company executives understood that producing the game without paying the actual players would risk further litigation. NCAA rules prohibited such payments, so the game died.

When states passed laws requiring the NCAA to allow NIL payments starting in 2021, teams realized they had a chance to bring the game back. EA Sports announced the game's return several years before its release, presumably to build enthusiasm for the elusive big NIL contracts. Ultimately, EA Sports executives decided to offer $600 and a copy of the game to any player who wanted to participate.

Opt-ins trickled in for the first few days. Then the dam broke and people started signing up by the hundreds. Now, nearly every player from the 134 FBS teams is in the game. Kennesaw State is also welcome. (Texas backup QB Archie Manning Not particularly.

Taking all of this recent history into account, Holt delivered one of the most understated statements of the century.

“The sport has changed a bit over the last 10 years,” he said.

Just a few. Free transfers and name, image and likeness payments have fundamentally changed the way the sport operates. Plus, the changing legal environment that once made it impossible to produce the game (and has made it possible to produce it again) is still in flux. So the game's producers tried to do all they could to simulate the new world of college football recruiting and NILs. But they focused all their efforts on the aspects of the game that never changed. As always, they tried to make the most immersive experience possible. They want you to feel the wall of noise that an opposing QB must contend with as he leads his team to the student seats at Penn State. They want you to understand why one receiver ran the wrong route because he couldn't understand the QB's audible while the swamp dwellers yelled at him between second and third downs. They want you to be moved when players on both sidelines wave to the children's hospital during the first and second quarters at Iowa.

Every scene, every image has to be faithfully recreated, because they're all seared into the memories of fans who spent the best four years of their lives in these stadiums, or who bought season tickets after graduation and turned those four years into four decades. Plus, schools want to make sure everything is perfect, because they know an experience this realistic is a recruiting tool not just for their football program but for the entire university. That 13-year-old from Connecticut who loved tossing the ball with Connor Weigman at Texas A&M might end up applying to College Station four years from now.

Lead designer Christian Brandt doesn't need a reminder that players will have a keen eye for detail: Brandt is a Penn State graduate who had the Nittany Lion mascot hand out champagne bottles at his wedding. teeth Gamers realize something is wrong.

So Brandt and his team made sure each of the 134 team bands came into the game in the exact same formation that the real bands would take to the field. (Yes, Tennessee runs in a perfect T.) Over the past few months, Brandt has taken countless screenshots of the pregame scene in Alabama's tunnel, where Crimson Tide players gather under the sign “BE A CHAMPION.” Each screenshot from the game started to look like a video of the real Alabama team about to take the field. When the game and reality became indistinguishable, Brandt knew they were almost ready.

How far did the designers go to recreate the atmosphere? They hired stuntmen and built a custom, two-story ramp in a motion capture studio in Vancouver to recreate the Clemson players running (and jumping) down the hill at Memorial Stadium. In the same motion capture studio, they also built wooden replicas of the Commander in Chief Trophy, Floyd of Rosedale, Illibach Trophy, and dozens of other trophy game prizes. And don't worry: The winners of the Iowa-Minnesota game will be celebrated with a giant pig statue.

Of course, designers understand that different players care about different things.

Colorado's two-way star Travis HunterHunter, one of three players currently featured on the game's cover, was in grade school when the final version of the game was released. He liked playing for Oregon State and Florida State back then. When he visited EA Sports last week, he got to play for the Buffaloes. But he wasn't interested in the extravagance. When asked what he thought about the recreation of Ralph's run, Hunter laughed. He mashed the X button to skip past the scene and move on to the actual gameplay.

The gameplay will be familiar to those who have played past versions or continue to play Madden. While the infrastructure of college football and the Madden game are similar, the calculations the game makes during play are very different. “In college football, the difference between the best player and the worst player is much larger than it is in the NFL,” says design director Scott O'Gallager. So if you have a two-star freshman defensive end going up against an All-American left tackle, that end is likely going to get buried.

Running the ball in the new version of college football feels much more dynamic than in past or recent versions of Madden. It's easier to see individual blocks unfold, and ball carriers can react quickly to press and slip through open holes. The designers explain that the behavior of blockers and defenders has been completely redesigned. Whereas in the previous version there were multiple patterns of blocker and defender movement, the new engine allows the game to generate individual matchups. The outcome is determined by the player's rating (based on Pro Football Focus data), strategy, leverage and the situation. This creates a much more diverse set of results, which the designers hope will be closer to what real ball carriers see in the game.

Other changes will be welcomed by some gamers but derided by others. For example, in a read-option play, the controls have been changed so that gamers must press X for the quarterback to pull and keep the ball. If they press nothing, the QB hands off while engaged with the back. In previous games, you had to press X quickly to hand off, and if you pressed nothing, you kept. What's the reason for the change? A QB keep is an outcome that doesn't happen often in the real world, and the new command gives players more time to read the unblocked defender and determine the right course of action.

Throw power is now more adjustable, with a meter that shows exactly how much force the QB will throw with based on how long the button is pressed. A good QB can control their power more effectively than an inconsistent QB. Additionally, players have individual abilities. Texas QB Quinn Ewers, another cover player, has platinum-level pre-snap awareness. So if the defense is indicating a cover-4 shell, a message will pop up pre-snap informing the gamer that the defense appears to be playing cover-4 coverage (although this may be a fake).

And a new wear and tear feature will show exactly how hits are affecting players in-game. “Every hit matters,” O'Gallager says. “And not all hits are created equal.” While some gamers may want to play gunfights every time, the design team understands that desire is not unanimous. “This means we're dying on a hill of balance when it comes to gameplay,” O'Gallager says.

Some players, like Hunter, will jump right into the pure gameplay, while others will want to immerse themselves in the off-season world of the game. Dynasty mode returns, allowing gamers to become coaches and build their programs (while managing the transfer portal and recruiting), while Road to Glory puts gamers in the role of players on their collegiate journeys. Each comes with a set of dilemmas ripped from the news. Coaches must decide how much energy to devote to high school recruiting versus portal recruiting. Players must decide how to balance learning the playbook with brand building and classwork.

Are the coaches negotiating no-pay salaries with the players? For now. Haumiller said the designers are treading carefully in that world, not because anything is taboo, but because things change quickly and this version of the game has to stay relevant for a year. “Has things changed since we were in this room?” Haumiller joked.

*Maybe he wasn't kidding: While Haumiller was speaking last week, a federal judge ordered that the Fontenot v. NCAA lawsuit stay in Colorado rather than being transferred to the Northern District of California, where it would have been consolidated with House v. NCAA and other lawsuits.

Haumiller wants to ensure that everything in Dynasty mode is as accurate as possible, which is a tall order given the various forces pushing coaches in 2024. “It's the most complicated mode in a sports game,” Haumiller says. “Everything in college is so much harder than in the pros.” Haumiller, an avid listener of college football podcasts and reader of college football news, is constantly providing his team with tweaks to the decision-making engine that powers Dynasty mode. For example, last week he asked if the realignment would make it more likely that Group of Five head coaches would move to Big Ten or SEC coordinator positions instead of other head coaching jobs. The answer? Probably yes. So don't be surprised if some Group of Five jobs open up that way in Dynasty mode.

Haumiller is prepared for Dynasty Mode to be criticized in July. “Just do it,” he says, because when you're discussing college football secrets with the creators of College Football 25, you're going to find like-minded people.

Christian McLeod, the game's production director, is a Michigan State fan who played John Madden football for the Jets as a teenager because the team looked good in green and white. He left the Jets soon after Bill Walsh College Football debuted in 1993, and after college he took a job helping produce NCAA football. “A lot of us were devastated when the game went away,” McLeod said.

But thanks to a team that never gave up hope, the game is coming back with a vengeance, and many of our loved ones will be wondering where we disappeared to in the middle of July.