To what extent do interest payments eat into national income?

From WOLF STREET by Wolf Richter.

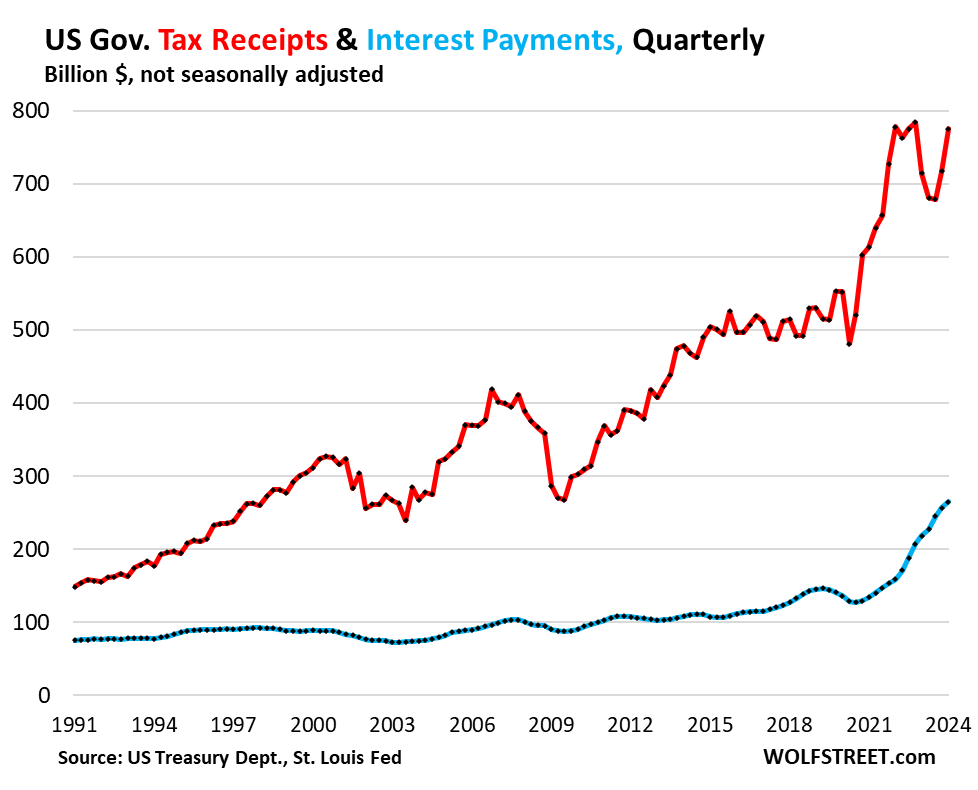

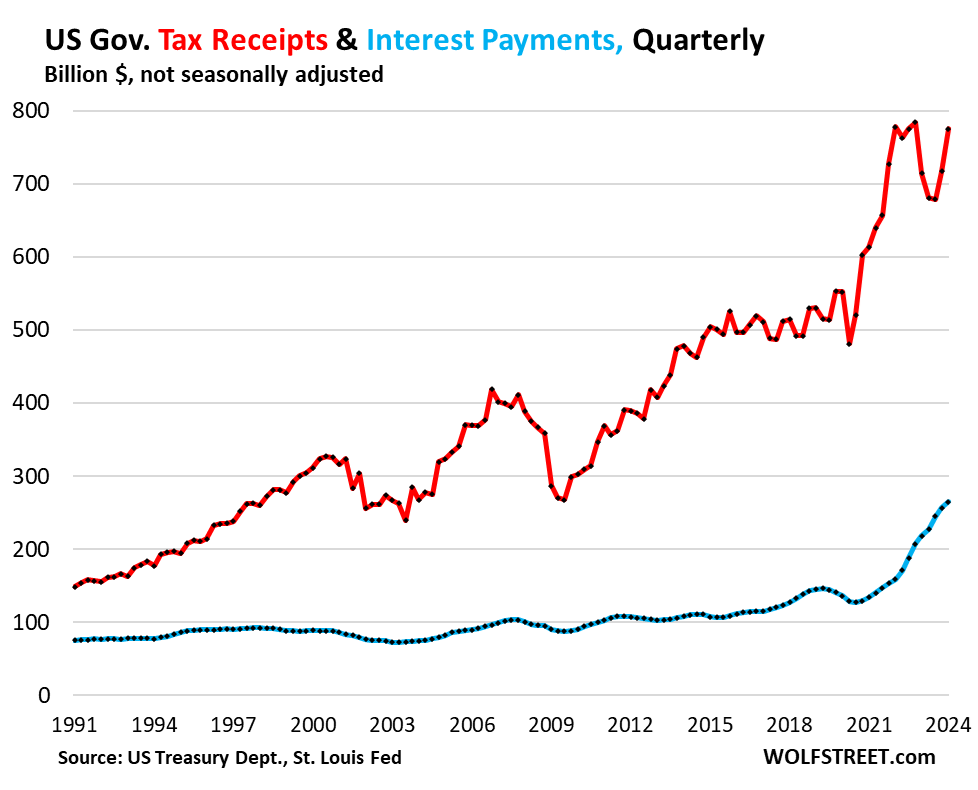

Tax receipt Federal taxes are looking pretty good in 2024. In 2023, capital gains taxes plummeted because 2022 was a terrible year for investors, so by the time it came time to pay capital gains taxes by April 15, 2023, there just weren't many capital gains on which to pay taxes, so tax revenues were terrible in the first and second quarters.

This year is different. By April 15th, capital gains taxes were due on gains realized in 2023. 2023 was a huge up year for stocks, bonds, and cryptocurrencies. That’s why tax revenues for the first quarter of 2024 increased by $60 billion (+8.4%) year-over-year to $775 billion (red in the graph below).

Other data shows second-quarter tax receipts have held up so far, partly because the national debt has not moved from $34.6 trillion for months despite the budget deficit rising relentlessly, and partly because the balance of the government's current account, the TGA, has surged to more than $950 billion in the days since April 15 due to an influx of tax payments.

Interest payments The government's ballooning debt balance rose by $46 billion, or 21%, to $264 billion (blue) in the first quarter from the same period last year.

In the 20 years between 1995 and 2015, interest payments barely grew even as the debt continued to grow, as interest rates continued to fall as part of the 40-year Treasury bull market that ended in August 2020.

The measure of tax revenue here is the amount available to pay regular government expenditures, including interest payments. This measure is total revenues net of contributions to Social Security and other social insurance, which are paid specifically by those who enroll in these programs and are not available to pay general expenditures. This measure of tax revenue was released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis on May 30 as part of its first-quarter GDP revision.

The reason for the sudden increase in interest payments:

debt The amount of debt on which governments need to pay interest has grown at an alarming pace in recent years.

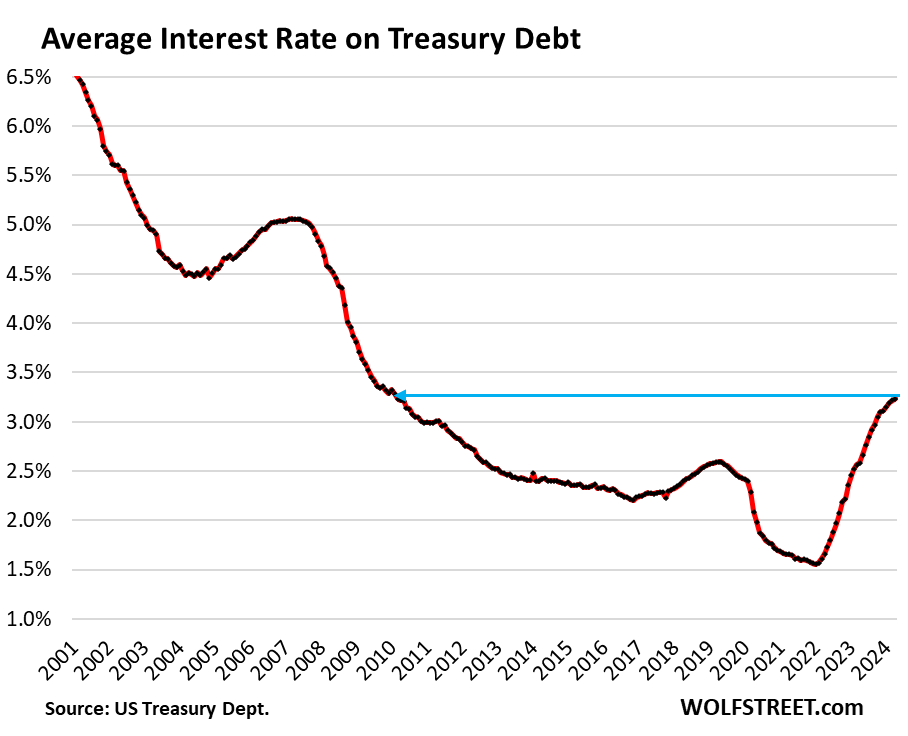

Rising interest rates The national debt gradually increases each time new Treasury bills or bonds are replaced as old ones mature, and each time the government issues new debt to finance a new deficit.

Treasury bills Treasury bills are constantly rolling over, and interest rates have remained above 5% for more than a year. Currently, of the $26.9 trillion in marketable Treasury bills outstanding, about 22% are Treasury bills, and the government is paying an average of 5.36% interest in April.

The average interest rate paid by the Treasury on its marketable and non-marketable securities holdings, totaling $34.6 trillion, in April was 3.23%. That's still low, and will likely continue to rise as current yields pile up on the debt mountain, but it was the highest it's been since early 2010.

What matters is interest payments and tax revenues.

The key is not interest payments in isolation, but interest payments in relation to tax revenues. Inflation and increased employment both inflate tax revenues: inflation inflates tax revenues by inflating taxable wages, and increased employment inflates tax revenues by having more workers earn taxable wages.

Higher interest rates also raise tax revenues because they generate taxable income not only from the $26.4 trillion in marketable Treasury bonds, but also from savings accounts, CDs, money market funds, and corporate bonds. American households and businesses hold trillions of dollars in these interest-earning assets. Households hold $3.6 trillion in money market funds, $1.1 trillion in CDs under $100,000, and $2.4 trillion in CDs over $100,000. In addition, households earn interest on other bond holdings, bond funds, and so on. All of this generates taxable income, whereas at 0% two years ago, it generated very little.

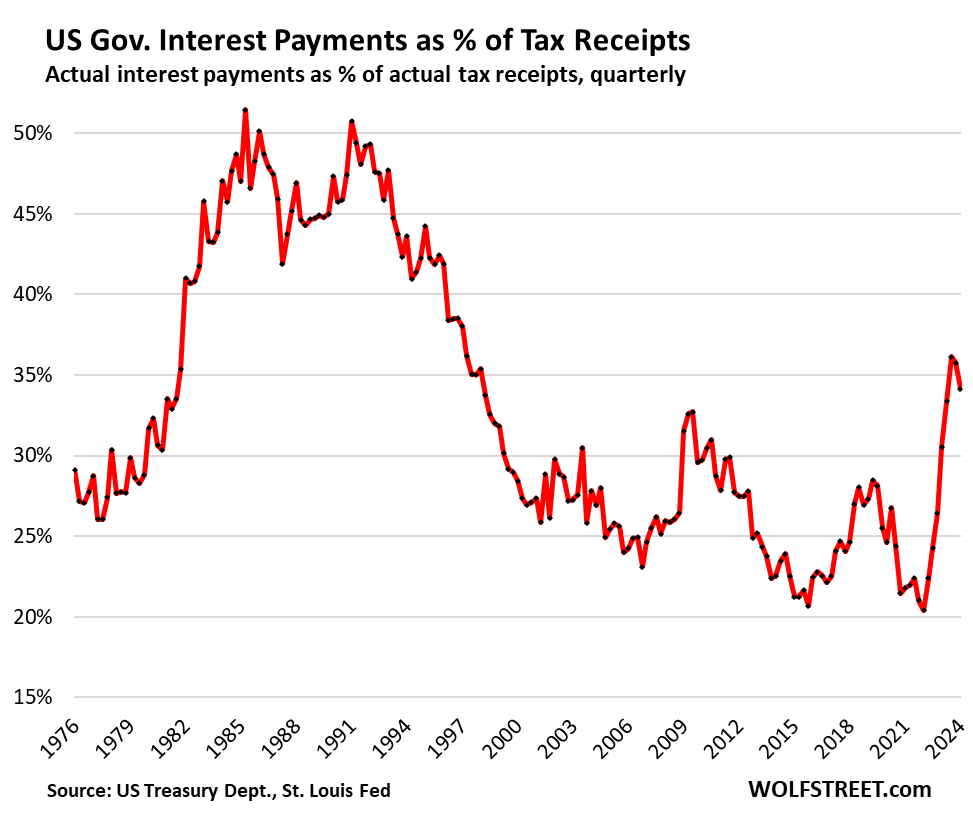

Therefore, the ratio of interest payments to tax revenue answers the question: “To what extent do interest payments eat into national income?”

In the first quarter, interest payments as a percentage of tax revenues fell to 34.1%. In the third quarter, it was 36.1%, the highest since 1997. The ratio also fell in the fourth quarter of 2023. In both quarters, tax revenues in dollar terms increased more than interest payments.

In the second quarter, this ratio is likely to fall further, before picking up and rising again in the third and fourth quarters.

In the 15-year period from 1982 to 1997, this percentage was higher than it is today, and in the 10-year period from 1983 to 1993, it ranged from 45% to 52%.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, interest payments were eating up about 50% of the nation's tax revenues, and the United States was heading toward a serious crisis. Congress, which decides fiscal issues, finally woke up and addressed the growing budget deficit. The budding dot-com bubble at the time also contributed to the expansion of the deficit by generating huge capital gains, jobs, and wage increases.

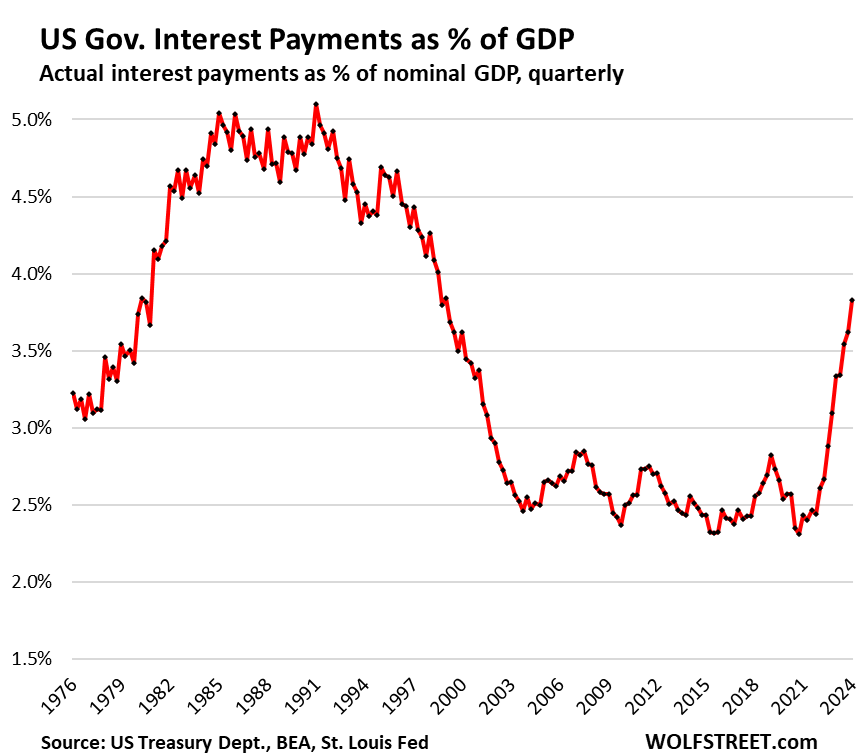

Interest payments are expressed as a % of GDP.

First-quarter interest payments jumped to 3.8% of GDP, the highest level since 1998. (This ratio is calculated on a like-for-like basis – quarterly interest expenses not adjusted for inflation, seasonally adjusted or annualized – divided by quarterly GDP of $6.93 trillion (nominal dollars, not adjusted for inflation, seasonally adjusted or annualized).

This is going inexorably wrong with disconcerting speed.

Higher yields will solve the demand problem.

Governments issue large amounts of new bonds every week. Someone has to buy these bonds, but if there aren't enough investors willing to buy them at the current yield, then yields will rise until there are enough investors who are attracted to the higher yields.

We all know what happened when 10-year Treasury yields briefly hit 5% last October: there was a massive buying frenzy amidst massive demand, after which yields fell again.

So there will always be enough buyers as yields rise until all the bonds are sold, drawing in buyers. But the problem is that as yields rise, interest payments skyrocket even more.

An undesirable long-term solution and outcome for an over-indebted government is inflation. Inflation has the effect of inflating tax revenues, reducing the purchasing power of old debt. It is much easier to repay old debt with devalued dollars. And there is every reason to believe that continued inflation will be the outcome and long-term solution this time around.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support us? You can donate, we'd be so grateful! Click on Beer and Iced Tea Mugs to find out how.

Want to be notified by email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()