The House, paralyzed by its most extreme members, passed just 27 bills to become law in 2023, a roughly 90% drop from the previous year. Republicans who see big government as a threat to liberty see this failure as a “success.”

But the idea of small government is a myth that is at odds with the history of the United States. In our new book, How Government Built America, we explore the extent to which the American government has intervened in markets since colonial times. It turns out that this country has always had big government.

18th century big government

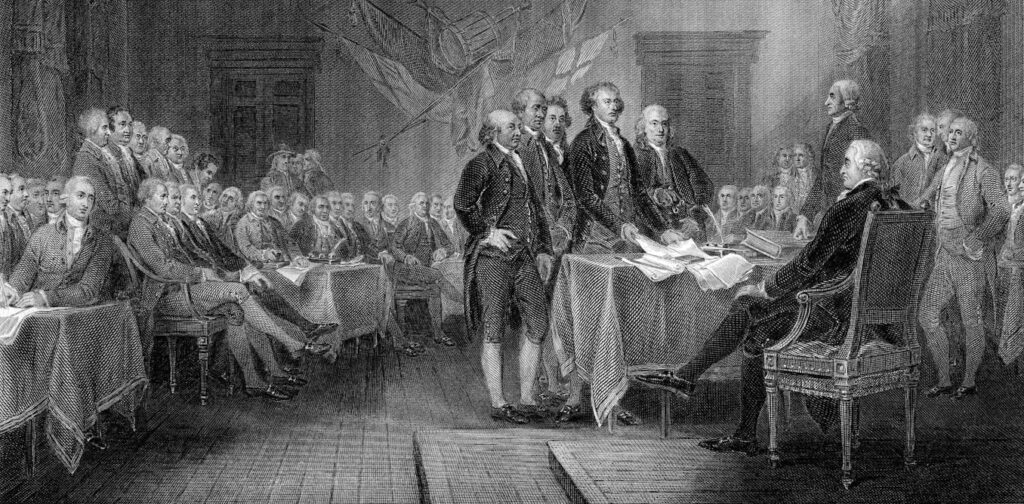

Small government advocates say the idea of limited government is fundamental to the United States. But the Founding Fathers, including those featured on today's $1 and $10 bills, called for the new government to intervene in markets.

Consider the situation in the late 18th century: After the United States won its independence from Britain, two political groups, Federalists and Anti-Federalists, struggled to divide power between the federal and state governments.

Federalists supported a strong national government, while Anti-Federalists opposed it. However, both sides agreed that the government should play an important role in the new nation. The Anti-Federalists were not opposed to strong government, but wanted to keep it at the local level.

Federalists, including Alexander Hamilton, George Washington, and John Adams, won. They led the federal government's efforts to manage the economy and invest in infrastructure, including building canals, bridges, and roads. To this day, the federal government continues to make similar investments to promote prosperity.

Thomas Jefferson and other Anti-Federalists believed that a strong, centralized federal government was more likely to become corrupt than maintaining local governments. In his inaugural address, Jefferson called for “a wise and frugal government that will restrain men from injuring one another, and otherwise leave them free to regulate their industries and pursuits of improvement.”

But Jefferson did not campaign against the widespread regulatory activity at the state level. At the time, nearly every aspect of early American economy and society, from Sunday worship to the opening of taverns, was regulated by the states, and before them, the colonies. This was “big” government.

Jefferson, like the other Founding Fathers, was influenced by republicanism (not to be confused with today's Republican Party), a political philosophy that understands the promotion of the public interest as a key goal of good government. These lower-case republicans put the government in charge of organizing economic and social activities.

Mr. Jefferson acknowledged that part of that government must be at the national level. As president, he supported key elements of the national government established by the Federalists, including the National Bank.

Three Centuries of Big Government

Similar patterns have played out throughout American history. Markets brought about the industrial revolution in his 1800s, but they also brought dangerous workplaces, products, slums, and poverty, which limited individual opportunity and threatened people's livelihoods. The federal government responded by taking over consumer market regulatory functions from the states for the first time, including railroad regulation, antitrust enforcement, and food and drug safety.

And when market freedom caused the Great Depression from 1929 to 1939, it was governments that restored economic opportunity and helped people live and work during that time.

More recently, when Wall Street crashed the economy in the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis, governments had to act again to restore the market. When COVID-19 broke out, the government rushed to develop a vaccine and restore people's freedom to live and work.

A question of values

We believe the myth of small government not only contradicts the reality of American history, but also threatens our nation's fundamental political values: We needed both markets and government to build a nation true to the American values of liberty, equality, fairness, and the common good.

For example, consider freedom. When individuals buy a car, start a business, or make countless other market decisions, markets are praised as promoting individual freedom. According to this understanding, market participants are free to make their own choices, and in so doing, the market will bring wealth and prosperity to the nation.

The Internet revolution is a good example. As entrepreneurs seek consumer attention and business, consumers have endless options for programming, software, podcasts, and other social media.

But history has shown that markets can also restrict the freedom of consumers and workers, thereby failing the public interest. Consider how the Internet can threaten the safety and well-being of children.

History shows that while the United States can shrink government at the demands of its most determined political opponents, the dangers posed by markets never disappear. For example, the world faces an “existential threat” in the form of climate change, a problem that the free market alone cannot solve.

The exact combination of government and markets has been debated throughout American history, and favoring “small” government has been a perennial campaign theme. But the idea, as far-right congressmen argue, that “big markets” unmonitored by “big” government are best for the country ignores centuries of American history.