More and more video games are seeing adaptations into movies, but Hundreds of Beavers might be the most video game-like movie I’ve ever seen.

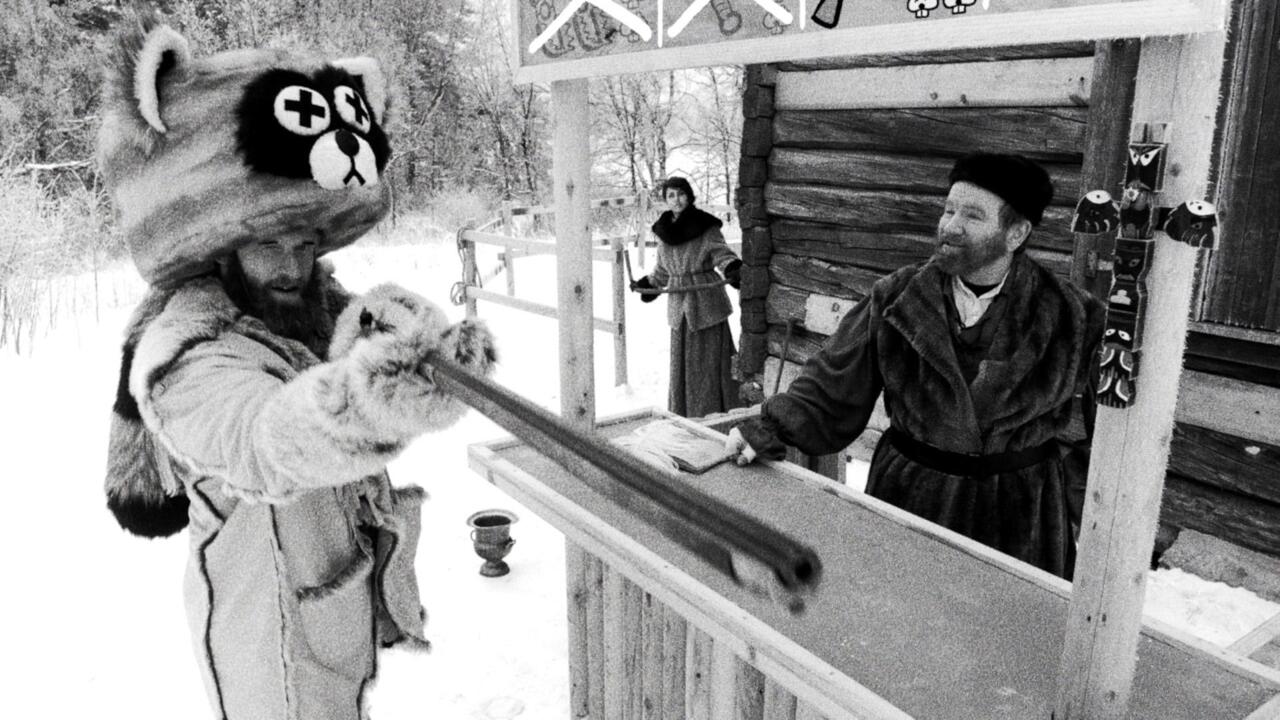

That’s not necessarily apparent from first blush, especially because Hundreds of Beavers’ other influences are so clear and stark. Following the story of a 19th-century fur trapper as he faces off against various woodland creatures in a wintery Wisconsin, it’s a black-and-white, mostly dialogue-free throwback to silent-era comedies, full of the kind of slapstick jokes that have made Bugs Bunny and Road Runner cartoons so enduring for so many years. It’s obviously channeling Buster Keaton, Tex Avery, and Chuck Jones, among a whole lot of others. Oh, and all the animals are played by average-sized adult humans in animal mascot costumes.

As it goes on, though, Hundreds of Beavers starts to work in gags that call back to video games. When the trapper, Jean Kayak (played by co-writer Ryland Brickson Cole Tews), finally manages to grab some of those mascot-costume furs, he sells them to a trader whose stand carries a game-like shop menu and sports music and sound effects reminiscent of the merchants in The Legend of Zelda series. Every time Jean manages to kill an animal, his “score” is briefly tracked on-screen. Later in the movie, there are very distinct references to Super Mario. It’s clear that Tews and director and co-writer Mike Cheslik are fans of video games, having previously cited inspirations like Super Mario Galaxy and Donkey Kong Country.

When movies take on elements of games, it’s almost always in a big, referential way. Adaptations such as Sonic the Hedgehog or Super Mario Bros. bring game characters into traditional film storytelling, with things like Sonic’s rings or Mario’s mushroom serving new story roles. Movies like Scott Pilgrim vs. The World or Free Guy use game elements as jokes in and of themselves–something you recognize as being “from a video game” and therefore funny or interesting through juxtaposition.

Hundreds of Beavers feels different because it uses the features of video games the same way it uses the features of cartoons. Menu-like icons aren’t popping up onto the screen to make you laugh at the use of a game idea in a movie context, but to convey particular information, just like they would in a game. In a way I’ve never seen before, Hundreds of Beavers uses the visual language of video games to inform its comedy, putting games on equal footing alongside its other slapstick inspirations.

The look, feel, and design of something like Mario or Hollow Knight is just as much at play here as the sight gags of Bugs or Buster.

“Even though there have been video-game adaptations over the last 10, 20 years, there haven’t been a ton of movies that have incorporated video game grammar in an interesting way into film, so we tried to do that,” Cheslik, who also edited the movie and crafted its visual effects, told me in an interview. “For me, growing up playing Mario and watching Buster Keaton from the library all at the same time, I view those as the same camera, a wide shot with no extraneous information. Just our hero, you know, his body in a wide [shot], you can’t really read his expression or emotions. He’s communicating with his body. And it’s a frame that’s about him and his physical obstacle, in kind of a locked-off frame.”

Most games are composed of long stretches that don’t carry any dialogue, where everything is conveyed physically and visually on screen, and that language transfers well to a movie like Hundreds of Beavers. Its use is most apparent in the second act, which fully takes on the spirit of something like an RPG.

Jean’s progress is conveyed through scene after scene of him setting traps, watching them fail, and iterating on his process, with tons of jokes along the way. As Jean traps more animals, he’s able to exchange the pelts for new items, like a knife, a rope, and a rifle, which he then uses to improve his traps and solve problems–a sequence that evokes RPGs and metroidvanias. Cheslik said the filmmakers intentionally designed the second act to be like watching a Let’s Play video, with viewers watching Tews “play the entire damn game.”

“It’s his Joseph Campbell hero’s journey, from being an alcoholic who could barely survive in the snow, to a man who is killing hundreds of beavers and facing the consequences for it,” Cheslik explained. “That journey of becoming better is not told in a truncated montage. It’s not told through elliptical edits of the Rocky montage of him getting better–you actually watch Ryland play the whole video game, you watch him catch every beaver, you watch him get every item and then apply those items to the levels, basically, of his loop.”

The movie also tracks how many beaver furs Jean has as he catches them like you’d see in a game. It plays as a visual joke, with a little beaver icon briefly popping up with a number beside it whenever Jean successfully defeats one of the semiaquatic rodents, but it also conveys his progress and advancement in skill.

“The idea of an inventory of a protagonist in a movie, having a consistent inventory, is fun to me too,” Cheslik said. “And I don’t know other movies that have done that. I think James Bond and any kind of, like, Chekhov’s gadget is like an inventory where you get your item from Q and it pays off later. But in our case, we’re also keeping track of the money of the number of beavers he has at any point, and then he spends it on items and it goes back to zero. I don’t know if that’s been done in other movies, but we just love that from games.”

Something else that works to the advantage of Hundreds of Beavers is how elements in games that players may otherwise find unremarkable can be funny in other contexts. When Jean climbs a tree, he shimmies up the trunk with Nintendo Entertainment System Mario-like moves. Those animations aren’t necessarily funny when Mario does them, but when they’re acted out by Tews, they become much goofier.

Game visual gags are everywhere in Hundreds of Beavers. A late sequence inside a castle-like beaver dam has Jean sneaking around, avoiding the view of beaver guards and riding logs and conveyor belts just like something out of Ratchet & Clank or Oddworld. A later log-flume chase has the feel of something like Crash Bandicoot, complete with a joke in which Jean and some beavers leap over obstacles while running atop a spinning log, only for one beaver to jump much too early, exactly like “in Mario Party when your friend jumps too early and Luigi eats shit,” Cheslik joked.

Even the logic of some story elements has a video-game feel, and Hundreds of Beavers consistently finds what’s hilarious about something that players might take for granted. At one point, Jean steps on a pine cone that goes straight through his bare foot, causing him to scream in hilarious pain. Soon after, though, he realizes he can use the strength of his voice to drive rabbits out of their underground warrens and into traps. Jean doesn’t just shout into the tunnels, though–he steps on another pine cone, deliberately this time, to create the desired effect. It feels like the solution to an old Sierra or LucasArts adventure game puzzle, something that’s just one step beyond intuitive, and the joke of seeing Jean turn a negative experience to his advantage heightens the payoff.

Another gag has a trap with a spiked log that spins like a pinwheel, meant to swing down from above and nail its quarry. Of course, things go awry, with the spinning log speeding up so much it works like a fan. Later, Jean uses the fans to create channels of flowing air to trap even more beavers.

“I just did that last night in Animal Well,” Cheslik joked when I mentioned the fans’ game-like logic.

Cheslik said he and Tews didn’t do any research to make those kinds of jokes–they were just the sort of things that were already in their heads from a lifetime of playing games.

“It’s not that we played every game, but we really liked the games that we have played,” he said. “Like the merchant stand, do you need to go back and play [The Legend of Zelda:] Ocarina of Time to remember how that works? That stuff’s just in there.”

What’s fascinating about watching Hundreds of Beavers as a fan of games is how well elements of the medium fit right alongside the more-traditional inspirations–the cartoons and slapstick comedies–for this kind of movie. When I pointed out how the log-flume chase felt like Crash Bandicoot, for instance, Cheslik noted that also draws from Wallace and Gromit. A generation of filmmakers have grown up with video games occupying the same space for them that Looney Tunes, Hanna-Barbera, and the Three Stooges did for older generations.

Cheslik said that, growing up, he loved the comedy of something like Mario Kart 64’s Block Fort map, which focuses on battling other drivers rather than racing. Because of the layout and huge number of reflective surfaces, it’s not just other players who are dangerous on Block Fort; any shells you fire can bounce back and hit you, and often shells go ricocheting around the map to be forgotten before they return at inopportune times.

“There’s a gag [in a Road Runner cartoon] where Wile E. Coyote is using rockets, and then we move on to some other premise for a while, and then one of his rockets comes back,” he said. “And I remember being, like, five and it blowing my mind that, ‘Oh, it’s like in Mario Kart when it keeps track of your shell and your own stupid shell comes back and hits you.’ So I’ve always felt that the Looney Tunes logic and Nintendo logic were the same.”

Games have always shared a lot of DNA with movies and drawn on the elements of the film as developers have spent the last 50 years experimenting with how games convey their experiences and tell their stories. The flow of inspiration has largely been one-way, though, and one major criticism of games over the years is that many try too hard to be movies interrupted by gameplay.

It’s not that movies should be more interactive, Cheslik said, but there are definitely inspirations and ideas from games that can work well in movies, just like games have made use of the techniques and visual language of film.

Cheslik spoke a lot about enjoying and being inspired by indie games in particular–games that find their own way by making creative use of their limitations. They develop a distinct identity by revitalizing older genres, using less graphically intensive visuals, and focusing on elements that are unique and specific to games.

“Indie games sort of accept what a game is, and try to heighten on one gameplay premise in an interesting way,” he said. “And I feel like the silent era in film was this early period where film was its own form, and it wasn’t yet just plays being covered by cameras. It was its own unique art form for 15 years. And obviously, sound had to happen, but big questions were being asked early on about what this new form is and what only it can do. And I hate to see games settle into a pattern of just iterating on what’s worked. It’s a special period early in an art form when people are asking big questions about what that art form is, and I like indie games that accept what a game is and don’t try to be movies.”

Cheslik said that Hundreds of Beavers is a lot like the filmmakers trying to do the indie-filmmaking equivalent of indie-game development.

“Early on, we were talking about indie games a lot,” he explained. “I really like the super tightly designed, self-contained indie game that picks a lo-fi style and is made by like three people. That’s what we tried to do with Hundreds of Beavers. Instead of imitating a AAA game, instead of imitating the look of a Hollywood movie, we picked an old style that we could achieve more easily with our small team, and so that every crazy idea we had could be included because we were only responsible for doing it in pixel art–or in our case, grainy silent black and white.”

Indie movies can take a page from indie-game development, Cheslik said, by distancing itself from the output of Hollywood in the same way that indie games take a different tack from AAA games. Leaning into older aesthetics, like Hundreds of Beavers does by channeling silent movies, or drawing from the visual grammar of games and other rising outlets of artistic expression, such as social media, are ways that indie films can set themselves apart.

“I hope that instead of imitating Hollywood movies, I hope that indie film picks different aesthetics. Maybe they’re archaic aesthetics, maybe they’re just simpler ways of conveying something visually,” he said. “Accept that you don’t look like a Hollywood movie, and then make something interesting in an indie style, the way that indie game developers do. Indie game developers pick a style that fits their resources, and they can still make strong images without $100 million.”

You can rent or buy Hundreds of Beavers on Apple TV or Amazon Prime Video. Check out the movie’s website for more info.