There’s one topic that’s stayed on my mind since the Game Developers Conference in March: generative AI. This year’s GDC wasn’t flooded with announcements that AI is being added to every game — unlike how the technology has been touted in connection with phones and computers. But artificial intelligence definitely made a splash.

Enthusiasm for generative AI was uneven. Some developers were excited about its possibilities, while others were concerned over its potential for abuse in an industry with shattered morale about jobs and careers.

AI has been a common theme at GDC presentations in years past, but it was clear in 2024 that generative AI is coming for gaming, and some of the biggest companies are exploring ways to use it. With all new technologies, there’s no guarantee it’ll stick. Will generative AI flame out like blockchain and NFTs, or will it change the future of gaming?

Doubts about the new next big thing

In prior years during GDC, San Francisco’s Moscone Center convention venue was awash in banner advertisements from game companies touting their use of the latest trendy tech: cryptocurrencies, blockchain, NFTs and Web 3.0. This year was no different, with ads from smaller companies expounding on their AI integrations.

Gaming’s biggest companies are still hesitant to commit to including AI in their plans. Nvidia and Ubisoft showed off their dynamically responding nonplayer characters at GDC 2024, but they haven’t announced grand plans to integrate them into upcoming games. Microsoft announced last November that it’s partnering with Inworld AI to develop AI game dialogue and narrative tools. (Inworld is the company Nvidia and Ubisoft teamed up with on their AI NPCs.) But the only generative AI that Microsoft is rumored to be developing is an Xbox customer-support chatbot.

There’s a lot of nervousness before the storm in the games industry, said Laine Nooney, assistant professor of media and information studies at New York University, but though the companies behind generative AI make daring promises, most of those promises probably won’t pan out. Hallucinations may be acceptable in ChatGPT responses, but not for video game narratives.

“These technologies seem poised to expand gamer expectations, even as I think companies underestimate how much additional labor they would require to be functionally productive,” Nooney said.

Still, Nooney is confident that AI will play a strong role in game development behind the scenes, citing a presentation by modl.ai that proposed how AI bots could hunt for glitches and bugs to help human-staffed quality assurance teams. Nooney recalled the modl.ai presenter offhandedly remarking that QA bots don’t need to go home to eat or sleep and can work all weekend. That’s a phenomenon that could potentially lead companies large and small to divest from human-led QA testing.

“It’s very easy to see how tools such as this might remove human-led QA testing entirely, especially from games on the lower to mid end of the cost or quality spectrum,” Nooney said. “And it encourages companies to build games of large scope that they would never be able to effectively test with human labor power — just reproducing the same draining labor dynamic.”

Indeed, in a year when game companies have fallen over themselves to lay off a historic number of employees, Moscone Center was haunted by anxiety over AI’s impact on the gaming industry’s workforce. In a roundtable for writers and narrative designers, people expressed concerns about the fragile state of employment beyond a few years, and the worry that AI would take even more jobs added fuel to the fire.

At GDC 2024, Nvidia showed off its in-progress NEO NPC (non-player character) technology for players to speak with and get generative AI-created responses.

Using generative AI behind the curtain

Artificial intelligence and machine learning were the focus of numerous GDC presentations. Some of these were sponsored by companies as unsubtle boosterism of the new tech, including Nvidia’s wild and curious generative AI experiments with nonplayer characters and performance-enhancing tools.

Read more: Chatting With Nvidia’s Generative AI Characters Felt Like Next-Level D&D

There were other talks led by developers explaining how they used generative AI to help production.

These technical talks illustrated scenarios where AI could generate suggestions or solutions that could save developers time, optimizing a small slice of the game production pipeline. One presentation laid out how developers could use AI to generate dozens of maps in a game dungeon or Mario-like platformer levels. An Electronic Arts developer explained how AI could improve the photorealism of faces on digital characters.

A talk by developers at Unity (the company behind one of the major engines used to make games), explained how the tech could be used with behavior trees. Submitting prompts to generate content could reduce the amount of tedious tasks on developer checklists, make it easier to use complex tools, and eliminate bottlenecks by letting developers iterate on gameplay without programmer support.

Automating granular tasks could speed up production time and free developers to spend time creatively ideating instead, said Unity Senior Software Developer Pierre Dalaya and Senior Research Engineer Trevor Santarra. Future game developers could use this approach to improve their workflows, especially in areas of game design that use natural language and can be submitted as AI prompts.

“We expect to see similar workflows used for creating new game rules and mechanics, orchestrating NPC and player interactions, as well as designing dynamical systems which bring virtual worlds to life,” Dalaya and Santarra said over email.

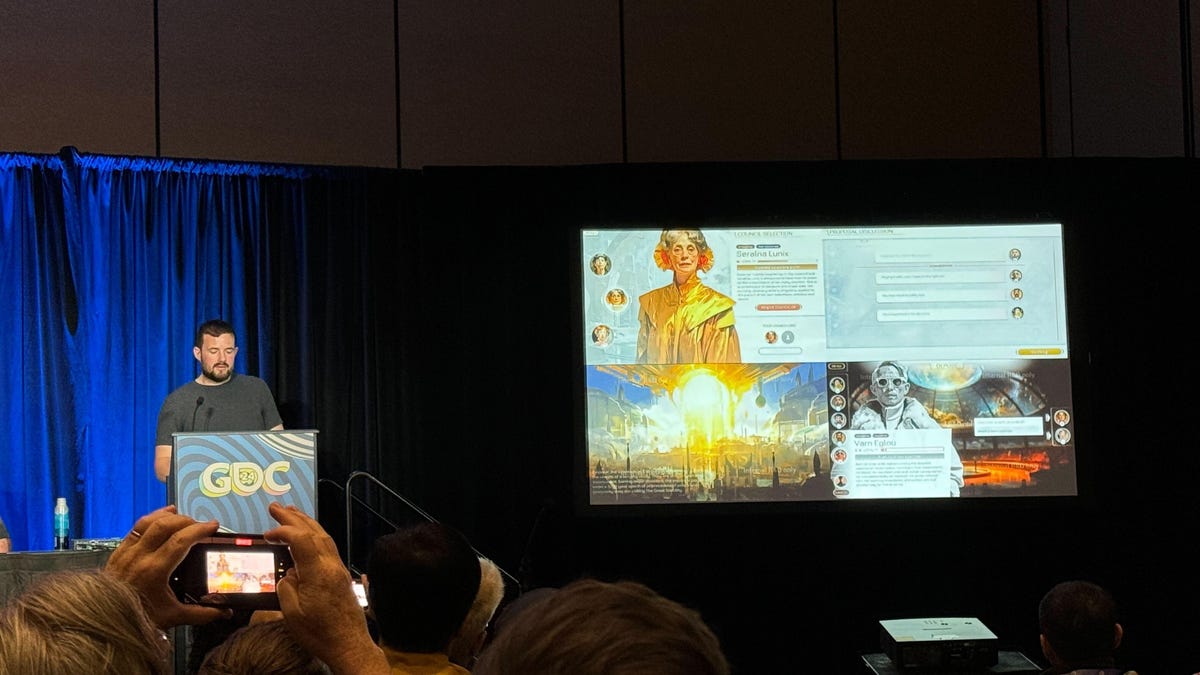

Leaders at Keywords Studios, a large firm that helps companies build games from concept to release marketing, spoke to a packed crowd. They presented findings on using around 400 AI tools to make their own experimental title, Project AVA, a sci-fi civilization-building game not intended for public release.

The experiment had mixed results. Rather than try out video created by generative AI, developers at Keywords used static 2D images for the visual look. They used Midjourney-like image generation tools and refined their prompts to get the Impressionist style they searched for. Ultimately, human curation was needed at every step, since periodic tool updates broke their prompts.

“I think generative AI can help if you really work with it,” Lionel Wood said during the presentation. Wood is art director of studio Electric Square Malta, under Keywords Studios, and helped lead Project AVA. It “still requires an artistic eye to curate and adapt generated artwork.”

Lionel Wood, art director of studio Electric Square Malta under Keywords Studios, presents on Project AVA.

The resulting generated art satisfied and impressed Keywords, but generative AI was far less successful at fixing bugs, frequently worsening issues. While it could produce static images, it was bad at creating layouts for user interfaces with menus and icons. With Project AVA in the rearview, Stephen Peacock, head of gaming AI at Keywords Studios, acknowledged that generative AI helped in ideation, coding and helping programmers adapt to using a new game engine.

“I think generally the perspective [after finishing Project AVA] was, if I was going to give sort of a star rating for generative AI in general: not ready,” said Peacock. “But there are definitely areas where we discovered that we did find the tools useful.”

Peacock was impressed by generative AI’s potential to help gamers create things within games, whether costumes for their player characters or custom maps to play in.

“Even five years ago inside Roblox or something, you have to dedicate time to really master these tools,” Peacock said. “And those tools are getting easier and easier to use, which allows more and more people to be creative, and that’s going to be very exciting.”

The experiment did result in some reassurance: Though Project AVA showed that generative AI tools can streamline some game development processes, Keywords concluded that they can’t replace human workers, at least not yet.

“For people who’ve been in the space for a long time, it was not a shocking result, but these tools can’t step in and replace people in the creative process,” Peacock said. And while he’s sympathetic to concerns, he feels they’re obscuring a larger potential for how AI tools will augment, not replace, workers. “What I think is often missed is that these technologies are going to allow us to do so much more.”

“While it feels like the pace [of new AI tools] is definitely picking up, I don’t think that’s anything new,” Peacock added. “That’s something people need to take reassurance from — is that creating stories and experiences is fundamentally how humans connect with each other, and the technology is just there to do that better, richer and deeper.”

Bigger than efficiency debates were Keywords’ legal and ethical concerns around making a game with generative AI. Would content produced by the generative AI tools be owned by the studio using them? (That’s a pertinent worry after a judge upheld the Copyright Office’s ruling that AI-created art isn’t entitled to copyright protections.) Could it be used in a commercial product? Would Keywords’ clients accept any risk of games worked on with gen AI? Would Keywords’ own developers feel ethically averse to using these tools?

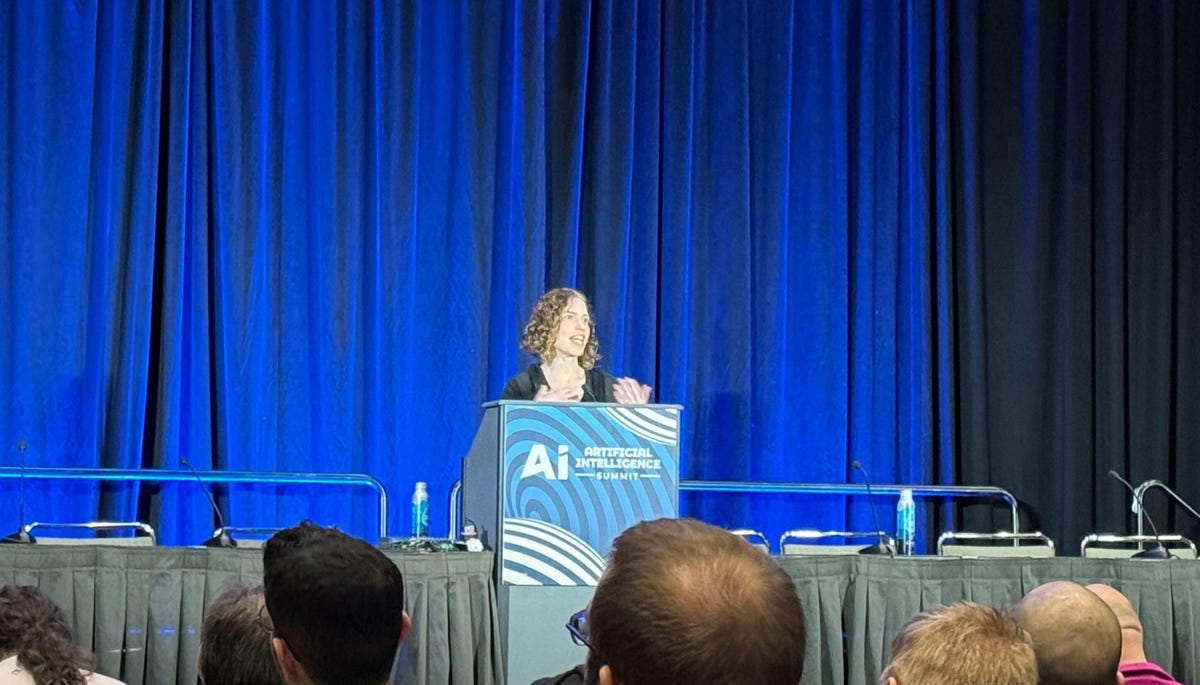

Hidden Door co-founder and CEO Hilary Mason presented at GDC 2024 about her studio’s use of generative AI to make narrative games.

What does this mean for gaming?

Most of the GDC presentations covered generative AI’s use behind the scenes, but a few explained how to use the technology as part of gameplay. Hidden Door developed its own game — currently in closed alpha — that actively generates new situations and characters for players to encounter and progress the plot, as co-founder and CEO Hilary Mason explained in the presentation.

Hidden Door’s game plays out like Dungeons and Dragons (or adventure video games) with players entering typed-out responses to situations. It’s similar to tabletop games in which players riff off of each other and see what happens, Mason explained.

“I think there is a whole class of experiences that become possible because of this tech, and ours is one of them,” Mason said.

Hidden Door’s game is based on standard genre stories, public domain books or the worlds of authors who partnered with the studio. Players can start an adventure in one of them and go in any direction, for instance, landing in the land of Oz (from the Wizard of Oz) and veering off the yellow brick road if they want. Hidden Door’s generative AI tech produces text and images of characters and obstacles that the player encounters in its 2D interface for the story to continue.

As generative AI technology advances, Hidden Door aims to refine its game system, potentially integrating things like animations and video, or switching to a visualized 2.5D or 3D interface with character models and environments. They also have to keep refining the biases that are inherent in all AI tools. During her presentation, Mason used Dall-E 3 and Midjourney image generation tools to make a photo of what it assumed the crowd would look like at her talk. It generated an image of an all-male crowd (inaccurate to the real attendees gathered in the room).

“It’s not to say we can’t use these models, but we then are responsible for mitigating that bias in our design,” Mason said.

Mason acknowledges the ethically fraught questions around the provenance of training data and explains that Hidden Door’s models are trained on data the company creates or synthesizes itself. Rather than ingesting tons of written works, it creates new works on the fly weighing different words and concepts according to the genre, so that if players are enjoying a cowboy frontier adventure they hopefully won’t run into any rocket ships. By design, they won’t run into words and passages lifted from previously written works, either.

Regardless, the industry will have to grapple with how games use large language models, which have ingested publicly available data for decades without concern until now, Mason said. “Nobody cared because we were not training the model to compete with the people who created the original data, and now we are.”

Playable indie games on display at GDC 2024.

Generative AI in gaming

Despite existential and legal concerns for generative AI’s presence in games, it may end up being used in far more mundane ways like other production tools, says Neil Kirby, a senior lecturer at Ohio State University’s College of Engineering who hosted a GDC AI roundtable discussion with developers. With this new tech, the games industry may just see a nominal productivity bump using its existing production pipeline.

“We’ve seen this before: when PCs invaded the desktop, every office worker in the world became far more efficient when the paper started going down and the electronic stuff came up,” Kirby said.

That specific transition also led to a mass reduction in the need for secretaries and personal assistants, Kirby acknowledged, and perhaps that’ll happen with generative AI as well. The changes he sees coming soon are more iterative than radical. For instance, AI tools could rapidly prototype textures and other visual elements for developers to stick in environments rather than leave them as neon surfaces (a typical early-development method before replacing them with finished work).

It isn’t just developers trying out generative AI tools; students learning the craft are using them, too. At Ohio State, Kirby’s seen GitHub Copilot become ubiquitous as a helper on computer science students’ shoulders, adding suggestions as they code their lines. The upside is the potential for better, uninterrupted flow as students use the tool to suggest solutions to roadblocks rather than have to break concentration to look up answers — a version of the tried-and-tested pair programming concept for coders flying solo.

This is worrisome as young learners lean on an AI advisor rather than learn the core disciplines of programming alone, Kirby says. It also introduces the potential for AI hallucination and other inaccuracies.

The genie is out of the bottle, and at least some students studying to get into the games industry are incorporating generative AI tools into their workflow. Throughout my time in the Moscone Center during GDC, presenters pitched their own ways the technology could change the way games are made, although there’s far from consensus on how it will be a net positive for game development given the legal murkiness and potential for inaccuracies. None of the conversations broached the enormous uptick in computation needed to use generative AI at the scale of the games industry, which would increase its already sizeable impact on climate change.

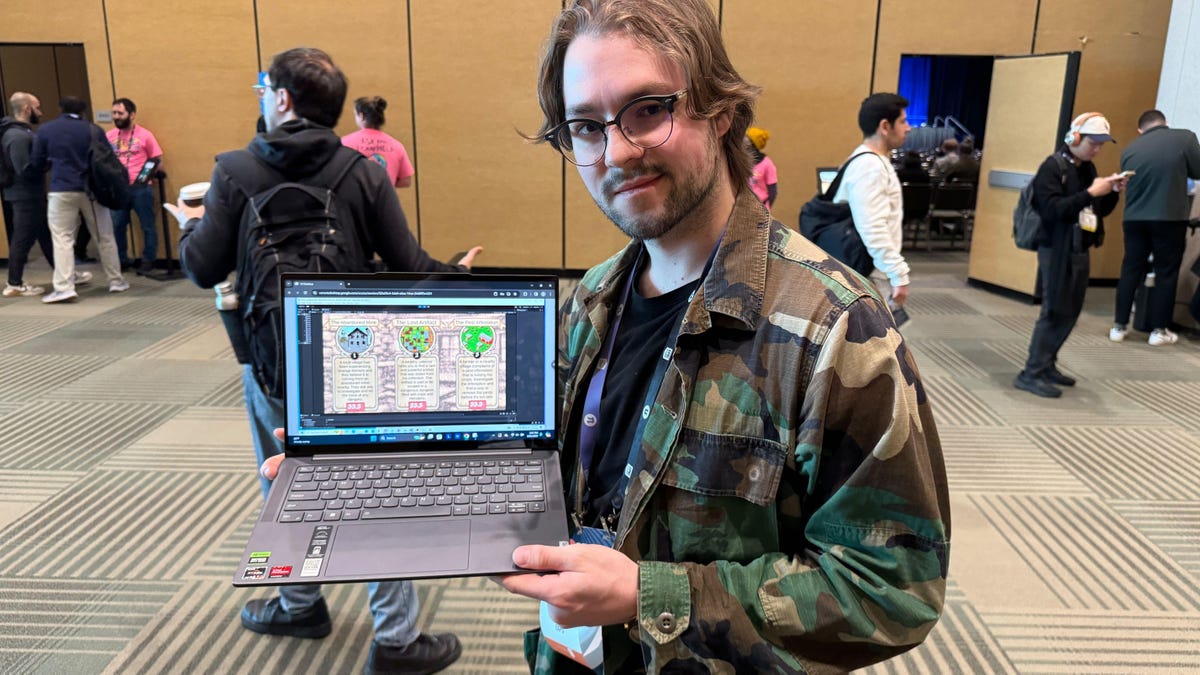

One attendee of the generative AI talks, Bryan Bylsma of his indie studio Startale Games, has been using generative AI to make games.

In the crowds who attended these generative AI talks was a glint of eagerness to use the new technology. Walking out of the Keywords Studios talk, Bryan Bylsma felt encouraged by the studio’s Project AVA proof-of-concept. A developer for heavy machinery simulation software, he’d been inspired by the automation capabilities of ChatGPT to dust off his college game development skills and, with a pair of friends, start using generative AI to make their own game.

“AI in general makes writing code that would traditionally take an hour and boils them down to five minutes,” Bylsma said. “It can make developing, especially on hobby projects, go super fast as long as it’s doing stuff that isn’t too complex.”

Bylsma recently put that to the test in his day job, using Unity’s Muse generative AI co-pilot tool to rewrite his workplace’s whole networking system in a week when it otherwise would’ve taken a month. With his friends, Bylsma formed the indie studio Startale Games to make a choose-your-own-adventure game that used generative AI tools to gin up plot text, characters and images on the fly. They’re having fun and don’t plan on releasing it commercially, given the legal uncertainties around the data provenance of the tools they use.

Being at GDC has given Bylsma and friends more ideas for their next game, as well as encouragement that they’re riding a trend wave. They met other devs who were similarly inspired to start making games with generative AI in the wake of ChatGPT and could be close to releasing those games to the public.

“That’s so funny because we started at the exact same time [as other devs]. Everyone just sees the writing on the wall of like, ‘hey, this thing’s gonna be really big,'” Bryslma said.

Editors’ note: CNET used an AI engine to help create several dozen stories, which are labeled accordingly. The note you’re reading is attached to articles that deal substantively with the topic of AI but are created entirely by our expert editors and writers. For more, see our AI policy.