Chicago (CBS) — A woman takes a photo on the street. She is a contract employee who investigates cell phone towers. A student seeks help from a career guidance counselor.

These are all seemingly routine activities. A snapshot of life across Chicagoland. All of them were reported to the police as “suspicious persons.”

They are then documented by local law enforcement in the form of suspicious activity reports (SARs), which are maintained by the FBI. A clear disparity is that most of those reported were Arabs and Muslims.

The nonprofit Arab American Action Network (AAAN) sued the Illinois State Police over hundreds of these SARs. CBS Chicago reported in 2022. They were looking for data that might validate experiences of discrimination and police surveillance, anecdotes they had heard from Arab communities for decades.

The report showed that is exactly what is happening. After state police agreed to release more than 200 of these documents through a settlement agreement, AAAN said the report had less to do with people's actions and more to do with their appearance. discovered. More than half of those reported as “suspicious” are described as “Arab,” “Middle Eastern,” “Muslim,” or “olive-skinned.” This is despite the fact that Arabs make up just over 1 percent of the state's population.

“That in itself proves our point that this is a tool of racial profiling and surveillance,” said AAAN lead organizer Muhammad Sankari.

CBS Chicago wants to find out how the suspicious activity reporting program was being used nearly two years later, especially as reports of hate crimes and racial profiling have skyrocketed since the start of the Gaza war on Oct. 7. That's what I was thinking. Illinois State Police even warned the public. “We remain vigilant,'' he said in a December news release.

“If you see anything that looks out of place or someone acting that doesn't seem right, please call your local police department,” state police said in a news release.

However, the agency has refused to release any more SARs to the public. State police have denied repeated Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests from CBS Chicago for more recent reports showing why people were being reported and their demographics, both before and after the Gaza war. And the Illinois Attorney General's Office said the denial was completely legal.

“Our community has a right to know if we are being targeted,” Sankari said. “Again, we knew that was the case, and we can confidently say that we still do.”

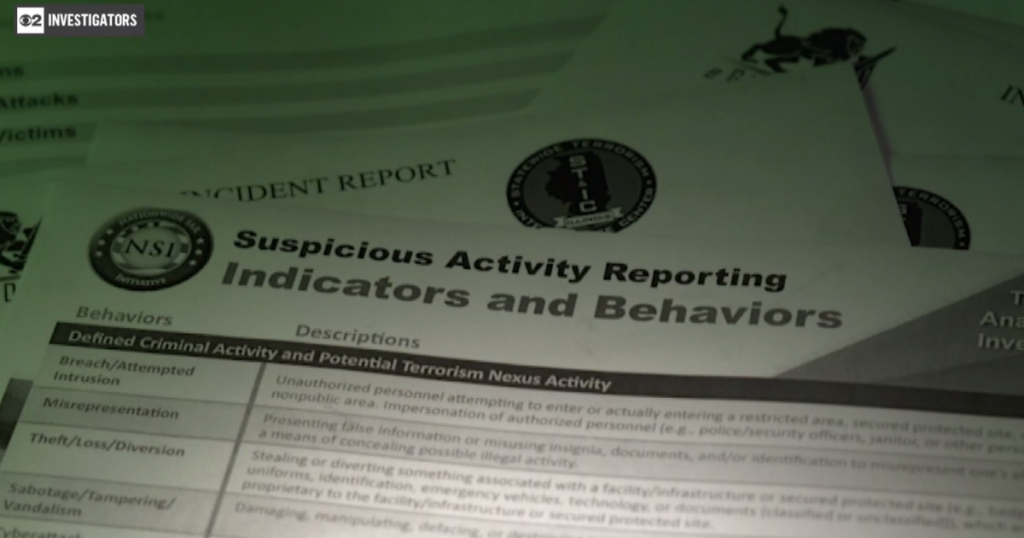

SARs are created as part of a federal program called the National Suspicious Activity Reporting Initiative. The program is administered by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the FBI, and he is one of many created in the years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

Reports of suspicious activity were specifically cited as necessary to thwart future threats. According to minutes from a DHS committee hearing, $2 million was allocated annually to the program in 2007, when the program was created.

The government asks and encourages the public to report any activity that appears “suspicious” or threatening to local law enforcement agencies, according to its website. This could be anything as vague as taking photographs of people or buildings “in an unusual or clandestine manner that would give rise to suspicion of terrorism or other crime to a reasonable person.”

Information about threats, including SAR, is received and analyzed by state-owned and operated facilities called fusion centers. These organizations serve as centers for collecting, analyzing, and sharing this information across states and major metropolitan areas. There are two of his fusion centers in Illinois: the Illinois State Police and the Chicago Police Department.

For example, in 2016, someone reported a “suspicious male, possibly of Middle Eastern descent” at the L station across from Wrigley Field. The suspect “appeared out of place while taking various photographs,” the report said, “possibly in Arabic,” the report said.

In 2019, police were called after a 16-year-old Orland Park student came to discuss concerns about the war in Syria. That same year, someone reported a black woman filming a video at the state capitol in Springfield for “wearing clothing consistent with clothing worn by women of the Muslim faith/religion.”

According to AAAN's analysis, SARs were created for each of these common everyday activities and hundreds of others from 2016 to 2019. This means that the FBI maintains a permanent record of these individuals, including their names, addresses, etc., even if the report is unsubstantiated.

“We were able to prove [in 2022] Look at the reality of the situation,” Sankari said. “We can do this and we should do it again. And I believe we will come to the same conclusion.”

To find out, CBS Chicago filed a FOIA request with state police, asking for more recent reports from 2020 to 2023.

Police denied the request, saying the records contained “criminal information” maintained by the FBI and could not be released.

CBS Chicago appealed the decision to the Attorney General's Office, which resolves or mediates FOIA disputes between citizens and government agencies.

CBS Chicago argues in its appeal that State Police has already released hundreds of SARs through previous settlement agreements and should be required to release similar records again, but with a more recent deadline. did.

However, the attorney general supported the state police's decision and said the agency did not unreasonably deny the FOIA request. The attorney general's opinion cites Illinois law and says CBS Chicago is seeking similar but not identical records to state police already released through the settlement agreement, so the agency does not have to provide them through FOIA. , he said.

Unless state troopers are sued again, the attorney general's decision means the public will no longer be able to see records of government programs that have come to light in the past regarding disparities. Matt Topic, a government transparency expert and attorney for the Loewys, said the legal system allows government agencies to release documents through litigation but refuses to release another batch of the same records through FOIA. He said the technicalities were “infuriating”. Affects public trust.

“It doesn't mean much to the average person,” he says. “That doesn't make a lot of sense to me. Otherwise, you're just cherry-picking what you want to release and playing the game with something that's very important. It means being transparent about what the government is going to do.” It brings sex.”

The state police said in a statement that the documents also contained personal information about individuals and “contains sensitive information that may pose a threat to public safety or violate an individual's privacy or constitutional rights. We are working hard to protect it.”

However, in previous SAR releases, police redacted personal information to balance privacy with allowing AAAN to see other contents of the report. In this case, CBS Chicago asked for similar edits to be made, but was denied.

A spokesperson for the attorney general did not comment specifically on the appeal, but said in a statement that Illinois law requires the attorney general to “fairly interpret” FOIA. The spokesperson also said the agency is “working diligently to educate public agencies about the records that must be disclosed in accordance with the provisions of FOIA.”

“With all due respect to the attorney general, I would like to say that they are wrong,” Sankari said. “Make no mistake, the public has a right to know. And, again, there are ways to release information that protect people's privacy.”

Topic also believes that the state police's privacy claims are inconsistent with the public's desire to know what is included in SARs.

“I don't think that reflects reality. I think people, especially those who are being surveilled based on ethnicity or religion, want the world to know that that's what the government is doing. '' he said.

“So you have this kind of strange situation where the government is making its own surveillance incomprehensible in the name of the privacy of the people being surveilled.”

Sankari said this also applies to Arab societies.

“If the Illinois State Police believe they are acting in the best possible manner without profiling, why aren’t they giving us information? [the records]? ” He said.

“Again, we're not asking for names or addresses. Why don't they just give us general data, demographic data, on suspicious activity reports?” Sankari continued. “To me, the answer is clear: Because they know, and we have proven, that this continues to be a practice of racial profiling.”

Sankari added that checking the latest SARs is now even more important. Since October 7, tens of thousands of people have rallied in Chicago and Illinois to protest Israel's killing of more than 30,000 Palestinians, according to figures from the Gaza Health Ministry. And Sankari said the FBI recently visited the homes of several people, including members of his organization and others who participated in the protests. He is concerned that they could be subject to false SARs.

“Obviously, the United States is involved in an aspect of the Gaza war, arming and financing Israel's genocide, and frankly, we believe that this crackdown is an important part of this ongoing “We believe this reflects an investigation into the communities that are speaking out against the war's genocide,” Sankari said.

“This leads us to believe that there are clearly far more resources, far more time, and therefore many more suspicious activity reports targeting our community being filed. ” he continued.

State Police told CBS Chicago only that 35 SARs have been reported since October 2023. The spokesperson did not provide details or say whether any of them were used to thwart a security threat.

The attorney general's decision to uphold the state police denial was also cited just weeks ago when the Chicago Police Department denied CBS Chicago's request for the very same records.

“I can say that we are very disappointed because we feel that this matter has already been litigated,” Sankari said. “If we want our communities to be safe, those who police our communities should be held to the highest standards of transparency.”