Scott Elder has a pretty typical morning routine. He wakes up at 7 a.m., drinks coffee and feeds the dogs, Bella (a rat terrier) and Spencer (a Chihuahua). But on Jan. 12, 2022, Elder’s routine was interrupted by a concerning phone call.

Elder is the superintendent of Albuquerque Public Schools in New Mexico, and the call came from his district’s IT department, saying they had found some sort of computer virus.

He recalls thinking, “Oh, we’ve got a bug in the system and they found it so they’ll just kill it and we’ll be done, right?”

The bug was in the student records system. So Elder’s IT staff shut that network down. But that meant teachers wouldn’t have access to basic information about the almost 70,000 students enrolled in New Mexico’s largest school district. Educators couldn’t take attendance, wouldn’t know children’s bus routes and were locked out of grading systems.

Meanwhile, IT staff was desperately trying to figure out whether the computer virus had spread to their health records, security system and payroll.

Over the course of the morning, Elder began to understand the enormity of the situation.

“I would say that I went from mildly disturbed at 7 a.m., to very concerned by 9 a.m., to sick to my stomach by noon because I was beginning to realize that this was not a one-day event, that we had a real problem.”

Then came the ransom demand for more than a million dollars.

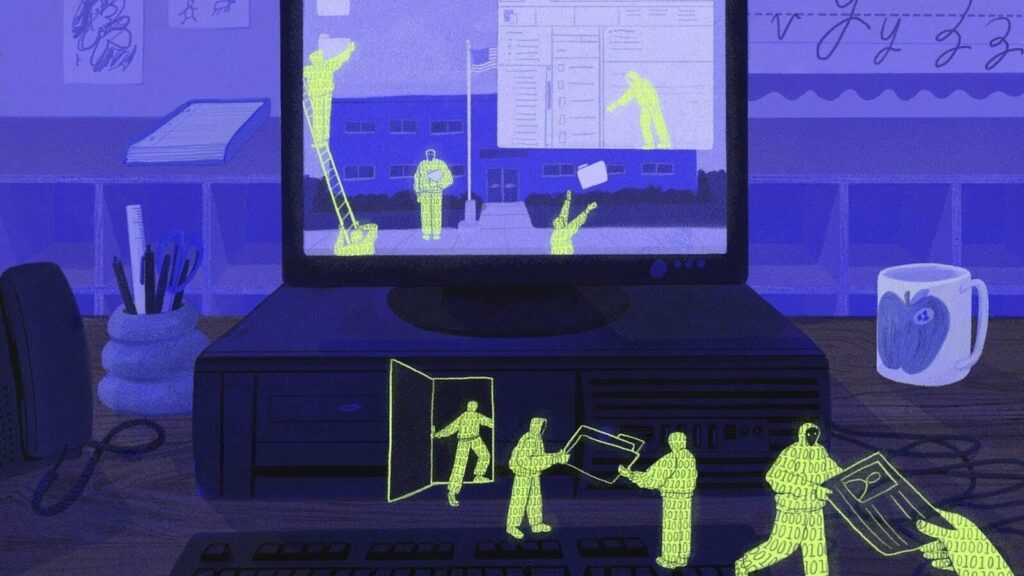

School systems of every size have been hit by cyberattacks, from urban districts like Los Angeles and Atlanta, to rural districts in Pennsylvania and Illinois. And the problem has been growing.

While it’s hard to know exactly how many K-12 school systems have been targeted by hackers, an analysis by the cyber security firm Emsisoft estimates that 45 school districts were attacked in 2022. In 2023, Emsisoft found that number more than doubled, to 108.

“The education sector has been and continues to be very heavily targeted,” says Brett Callow, an Emsisoft threat analyst.

Experts like Callow say these attacks are often carried out by hackers outside the U.S. They can involve ransomware, where hackers lock data up and demand payment to “unlock” it. They may also threaten to release data publicly if districts don’t pay up.

These attacks can also involve “Zoombombing,” where someone intrudes on a video call, often with pornographic or hateful images; denial-of-service attacks, which prevent or slow the use of networks; and phishing, an attempt to access data through fraudulent emails.

In many cases, sensitive data about students and staff – including social security numbers, sexual assault records and discipline information – has been stolen. Some of this information can be used to steal identities or redirect payments.

According to a 2022 U.S. Government Accountability Office report, it can take up to three weeks for classes to get back to normal after an attack; but behind the scenes, it’s taken some districts nine months to recover.

Schools are easy targets for hackers

One reason for the increase in attacks is that hackers have realized school systems are vulnerable. They often have older computer systems, rely heavily on technology and, Callow points out, “they don’t necessarily have cyber security experts on staff.”

In addition, schools are essential services, so superintendents are under a lot of pressure to resolve these issues quickly.

Schools are “low hanging fruit,” says Noelle Ellerson Ng with the School Superintendents Association, which represents 9,000 district leaders across the country. She says schools are often a community’s single biggest employer, and school systems collect a lot of data.

“That makes it very, very ripe. And then you layer on the fact that [the data] is so sensitive and so longitudinal and so personal, and there’s a huge vulnerability.”

What cyberattack crisis mode looks like

Elder, in Albuquerque, says in the middle of the attack, it was difficult to share information with the community.

The district was still trying to figure out what happened, and which federal and state agencies to contact about it. They needed the school board to sign off on hiring specialized cybersecurity contractors, and then they needed to bring those contractors on.

Most urgently, without the ability to take attendance and make sure all students were accounted for, Elder had to cancel school indefinitely.

Parents were furious.

“I said, ‘We’re not coming back until we know for sure it’s safe for kids,’ ” Elder recalls. ” ‘And I know that’s frustrating and I know you want a date, but I can’t tell you that today.’ ”

Elder was advised by the FBI not to share specific information with families because hackers monitor communications. And district leaders couldn’t use email because they didn’t want to risk spreading the virus. So Elder set up robocalls and did media interviews to get the message out.

In the end, the attack closed Albuquerque Public Schools for two academic days. Staff and outside contractors worked through a long holiday weekend, and schools reopened six days later, once they realized no financial or health information had been compromised, and the district’s backup systems were intact.

“We were a little wounded on that Tuesday, but we were functional,” Elder says.

The district made up the “cyber-snow days,” as they’re called, at the end of the school year.

Cyberattacks cost schools a lot of money

In 2022, cyberattacks cost schools and colleges an estimated $9.45 billion in downtime alone. That’s according to a report by the research group Comparitech, which is also quoted by the GAO.

And then there’s the cost of recovery.

According to Comparitech, Buffalo Public Schools, in New York, spent around $10 million on recovery efforts after it was attacked in March 2021.

Baltimore County Public Schools spent around $8.1 million.

The costs aren’t always that high – but they do often strain budgets.

When Olufemi Aina, the head of IT for Atlanta Public Schools, was told in 2017 that some staff hadn’t been paid, he started investigating. He learned that employees who had clicked on phishing emails a couple of weeks back had unwittingly given hackers entry to their payroll details. Hackers went in, changed the bank details and employee salaries were rerouted.

Aina says the first thing the district did was to make employees whole, so they immediately initiated bank transfers.

“People have to pay their bills while we were trying to figure things out,” he says.

Then the district had to hire outside technical experts to help understand the full scope of the attack.

“Some of those firms charge upwards of $400, $500 an hour. We took laptops from all the people that were compromised. We took forensic data captures of all of their hard drives. It was just a lot of man hours and a lot of effort and a lot of consulting time.”

From there, the costs just piled up. They paid for a retainer agreement with a security firm, bought cyber insurance, installed additional software and hired specialized staff.

One district estimate puts the total cost at about $300,000.

Callow, the cybersecurity expert, says even now many school districts don’t have basic prevention protocols in place. But it’s hard for leaders to make the case for spending on cybersafety when education budgets are already tight.

“Spending on cybersecurity wouldn’t necessarily be politically popular,” he says. “And schools often don’t have the expertise to know where they should be directing their money either.”

Elder, in Albuquerque, says his district was in the middle of getting quotes for cyber insurance when the attack happened. After the attack, their costs went up 300%.

“We felt fortunate that we found anybody to insure us at that time because I think most of the vendors actually pulled their proposals.”

School districts aren’t always eager to report cyberattacks

There’s no way to know just how many K-12 school systems have been targeted by hackers. According to the 2022 GAO report, that’s because school districts can be reluctant to report they fell victim to a cyberattack. In addition, experts say, the federal government doesn’t require that schools report cyberattacks.

Elder says the FBI told him the attack on his district was carried out by hackers overseas. He says he was surprised by the “ferocity and sophistication” of the operation.

“It’s not Johnny in his room trying to break in and change his grades anymore,” Elder says ruefully. “And we’re a school district. We weren’t equipped to go to cyber war with foreign nationals that are well funded.”

He says it’s a big problem when districts keep quiet about cyberattacks.

“They think it shows that you failed somehow. I don’t think that we failed. I think this is now a fact of life, and you better be prepared to address it.”

Aina, in Atlanta, agrees. He says after his district was attacked, they learned how many other school districts just in the Atlanta area had been the victims of similar cyber breaches. Atlanta Public Schools decided to be proactive and share information with other school districts.

“I’m sure that a few of them probably learned a thing or two and went back to their respective schools and made some changes,” he says.

What schools can do to prevent cyberattacks

There’s a lot school districts can do to build a “cyber aware culture,” says Cindy Marten, the deputy secretary of the U.S. Education Department and a former superintendent of the San Diego Unified School District.

The first step is to have complex passwords. The second is multifactor authentication, which means users have to enter more than just a password (a code sent to their phone, a fingerprint scan, etc.) to log in to their account. And the third is keeping software up to date.

“Those three things. If every district in the country did those things that don’t cost money … we [would] have a way to defend and protect our schools,” Marten says.

She says everyone should also get training so they know not to click on unknown or suspicious emails.

“Have you built this into your culture? It can’t just be the tech person. It’s got to be every teacher, every school secretary, every student that logs into any district device.”

Atlanta made everyone change their passwords to make them more complex. The district also made cyber security training mandatory for all staff, so everyone had to learn to recognize possible phishing emails and other safe practices.

Aina says there is no fail-proof way to keep information secure – it’s about putting as many layers of protection around data as possible.

“And that’s what we tried to do, put as many layers as possible between our secure assets and the bad guys.”

The White House convened a cybersecurity conference for some school leaders in August 2023, in which it connected schools with free resources. And the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is currently reviewing public comments on a proposal to provide up to $200 million to strengthen cyber defenses in schools and libraries.

“We’re making the resources available, educating, bringing superintendents together to educate them about the threat,” says Anne Neuberger, deputy assistant to the president and deputy national security advisor for cyber and emerging technology.

She says the White House doesn’t have the authority to require minimum school cybersecurity protocols, like they can with rail, airports and pipelines.

“So we’re doing everything we can short of requiring, which we just don’t have the authority to do at this moment in time.”

Doug Levin, the director of the K12 Security Information eXchange, a national nonprofit helping protect K-12 school districts from cyberattacks, says these federal efforts are a good start, but they’re not enough, especially given the increasing scale and severity of the attacks.

“We need to move faster and with more conviction here. We think that we’re going to need a much more robust effort from the federal government to make progress on this issue,” he says. “Tomorrow is too late.”

It’s easy to be paranoid after a cyberattack

In Albuquerque, Elder’s district has beefed up security protocols. There’s ongoing training for all staff, including tests where the IT department sends out fake emails to see if staff click on them.

But some are so realistic, even Elder has failed one of those phishing tests.

In the past few years, he says, he’s become paranoid: He was invited to a cybersecurity summit at the White House, but didn’t believe that the email was authentic.

“I got the email and I went, ‘Oh, good one! This is a good one, right, I’m going to the White House!’ ” he recalls thinking incredulously. He reported the email to his IT department as a phishing attempt.

“Thankfully they got back to me quickly and said, ‘No, this is real.’ And so, yeah, I got to go!”

Elder says he’s trying to get everyone in the district to feel the same sense of urgency around cyber safety. Just because you’ve been hit once by hackers, he says, it doesn’t mean it can’t happen again.

Edited by: Nicole Cohen

Visual design and development by: LA Johnson

Audio story produced by: Lauren Migaki