More than four years ago, when India's Hindu nationalist government carved out Ladakh from Indian-administered Kashmir, the regional capital Leh erupted in jubilation. A majority of voters even voted for Prime Minister Narendra Modi's party to fulfill their long-term demands. They had accused the Kashmir-based leadership of discriminating against the Buddhist-majority Himalayan region, known for its snow-capped mountains and lush grasslands.

However, Leh's joy did not last long.

The government's decision to rule the region directly from New Delhi is a sign of the region's democratic marginalization, lack of voice in development projects, and the ecologically sensitive Himalayan region located at an altitude of 5,730 meters (18,800 feet). has raised concerns about militarization.

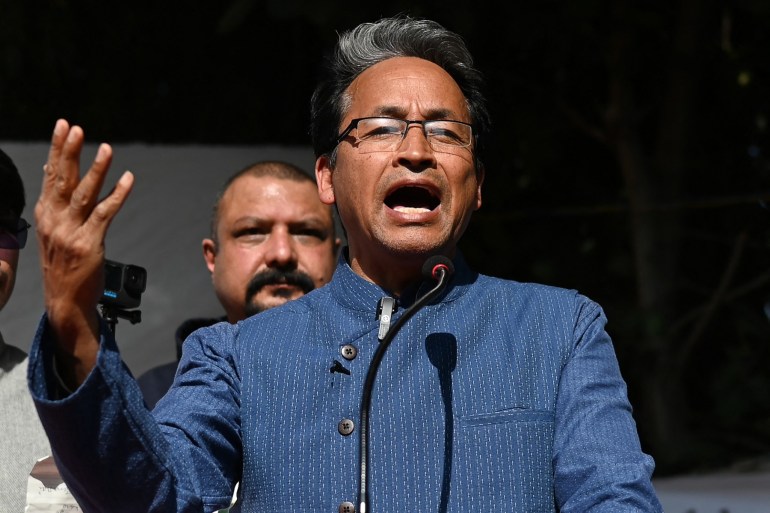

Hundreds of people gathered in Leh on March 6 after the latest round of talks with the interior ministry failed to yield results. Ladakhi activist Sonam Wangchuk has begun a 21-day fast to demand devolution of power and constitutional protection to fight the onslaught of outside influences that threaten the loss of tribal identity.

“I want to follow a peaceful method… so that our government and policy makers realize our pain and act,” Wangchuk said.

Who is behind the recent protests and what are their demands?

In August 2019, Prime Minister Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government abolished the special status accorded Kashmir and divided it into two federally administered territories: Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh.

But Ladakh leaders say they lack political representation in the current bureaucracy and have little say in development projects announced by the New Delhi-run government. A new law passed by the federal government that allows outsiders to settle and start businesses in the area is also causing concern for local residents.

The two autonomous bodies established in the mid-1990s to early 2000s for the autonomy of Leh and Kargil have now been stripped of many of their powers. The local body, known as the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council, played a key role in decisions regarding health care, land, and other local issues in Leh and Kargil districts.

People are taking to the streets to protest. Activist Wangchuk camped out in sub-zero temperatures and fasted for five days last January to highlight the threat proposed mining and industrial projects pose to the pristine environment.

On February 3, thousands of residents gathered in Leh, Ladakh's main city, under the leadership of the Leh Apex Body and the Kargil Democratic Alliance, which represents the aspirations of Buddhist-majority Leh and Muslim-majority Kargil. did.

They are demanding statehood for Ladakh. This is tribal status under the Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution, which allows for the formation of self-governing districts with some degree of legislative, judicial, and administrative autonomy within the state. They make laws regarding important things like land, forests, water, and mines. This is extremely important in a region where 97 percent of the population is tribal.

“As we are tribal and have a small population, it is very important for us to defend our rights,” Ladoor Lapp, a Leh-based student who sings protest rap songs, told Al Jazeera.

“We celebrated in 2019 thinking we were waiting for this moment, but in vain.”

A Hindi song posted by the rapper on YouTube has been viewed 69,000 times. The song is called '6th Schedule of Ladakh' and some of its lyrics are translated below.

My compatriots, listen to the voice of Ladakh. What's going on with this government when you can't even make a sound? We're not just chatting. Our home is at risk.

Representatives from both regions have held multiple protests and rallies in New Delhi to demand indigenous rights to land and jobs.

Nine rounds of talks between New Delhi and Ladakh leaders ended in a stalemate. The previous meeting held on March 4th did not produce any concrete results.

“We want democracy to be restored in the region,” Wangchuk, an educator and prominent voice in the current protests, told Al Jazeera.

Most Buddhists in Leh have long resented that the region's center of power is based 420 kilometers away in Kashmir's capital, Srinagar. When India stripped Kashmir of its semi-autonomous status and divided the region, Wangchuk said he expected Ladakh's parliament to be involved in decision-making. But that didn't happen. The government is headed by the Lieutenant Governor, who is appointed by the President of India. Under the current arrangements, the people of Ladakh feel more undervalued than ever.

Before Kashmir's semi-autonomy was revoked, outsiders were prohibited from purchasing land and settling in the region. But there are now growing concerns about potential demographic changes and damage to Ladakh's fragile ecosystem. Kashmiris have expressed similar concerns.

Residents said if the Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution is extended to Ladakh, it will protect it from demographic changes and resource exploitation by outsiders.

Even local Bharatiya Janata Party leaders support this demand.

“We stand with the people and also demand constitutional safeguards,” Bharatiya Janata Party leader Nawan Samsthan, who is from Leh, told Al Jazeera.

What are the environmental issues facing Ladakh?

Ladakh is known for its glaciers and glacial lakes, which are the main water sources for the region. Himalayan glaciers and the basins they feed are called the “water towers of Asia.” These are one of the few frozen freshwater resources in the world.

But residents said retreating glaciers and changing weather patterns due to climate change are leaving the region with water shortages, threatening their future. They said the increase in tourists is also straining limited resources.

During the peak summer season, the number of tourists exceeds the 274,000 locals. In 2022, in his first eight months, 450,000 tourists visited Ladakh. The government's plans to promote tourism and develop the area's natural resources are causing anxiety among residents.

According to reports, seven hydropower projects have been proposed and several industry groups have expressed interest in exploring the area, which is rich in minerals such as borax, gold, granite, limestone and marble.

Bids are also being solicited for solar power projects, and the Ladakh government is seeking permission to clear 157 hectares (388 acres) of forest to build power lines.

“The development project will bring some convenience to people, but no one is interested in this kind of development,” Wangchuk said.

“What is the point of development without democracy?” he asked, adding that Ladakh would become a playground for industrialists interested only in profits.

“They have no interest in the future or the local people.”

Over the past three years, India has been building its military infrastructure. Amid tensions with China over territorial disputes, the country acquired land for military purposes such as roads and bridges. Local residents who lost their land said they felt vulnerable.

“I can't say it publicly, but I want the military to be as sustainable as possible,” said a Leh-based activist who spoke to Al Jazeera on condition of anonymity.

The 35-year-old said the concerns of local residents were being ignored.

Why did the people of Kargil join the protests?

Kargil, about 200 kilometers (125 miles) west of Leh, wanted to be part of the divided Muslim-majority Kashmir region and faced political and financial discrimination against the Leh government. I've been criticizing it.

However, over the past three years, the region's political landscape has undergone seismic shifts. Leh and Kargil have teamed up in a move that many Ladakh analysts consider unprecedented.

Overcoming religious and political divisions, leaders from both districts are now united for a “greater cause”, which Wangchuk described as “a fight for Ladakh's identity”.

Sajjad Kargili, a member of the Kargil Democratic Alliance, told Al Jazeera that the people of Leh and Kargil are now on one page.

“Our fears about our identity, our jobs, our demographics were real and everyone in the region knew it,” he told Al Jazeera.

“It's not just the demographic changes, there's a bigger fear that our ecosystems will be destroyed.”